Today the Metropolitan Museum of Art opens “Monumental Journey,” a show featuring the work of the most famous photographer you never heard of, Frenchman Girault de Prangey. In the 1840s Girault traveled throughout the Eastern Mediterranean with over 100 pounds of photographic equipment, plates and chemicals; he returned with more than 1,000 daguerrotypes, the brand new visual medium he would help define at the very moment of its birth. His images, which the Met has curated in a gorgeously designed exhibit — the galleries have been darkened and the works lit from behind to minimize glare from the glass plates — are the earliest surviving photographs of Greece, Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Turkey, and Jerusalem. Many are historically important because they capture lost details and architectural elements: graffiti on Pompey’s Column in Alexandria, long since erased; the top tier of a minaret at Khayrbak Mosque in Cairo that disappeared shortly after his visit; a Frankish Tower in the Acropolis, demolished in 1875.

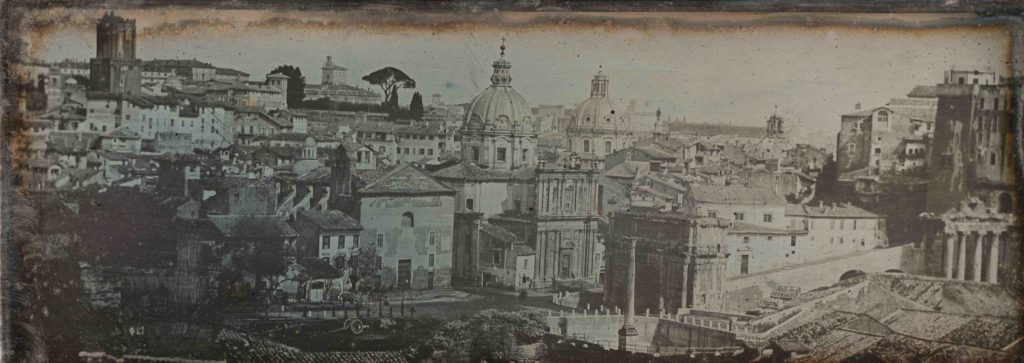

Girault was the first photographer to document the built environment, and like so many Romantic artists he was attracted to ruins: the Parthenon; Temples of Artemis, Castor and Pollux, Vesta, Vespassian, Nike; Hadrian’s Villa; the Roman Forum. He captured close-up details, like the capital of a column from an Egyptian temple, and also created larger landscapes like the stunning Roman Forum, Viewed from the Palatine Hill (1842):

Girault de Prangey (French, 1804–1892) Roman Forum, Viewed from the Palatine Hill, 1842 Daguerreotype 3 3/4 × 9 11/16 in. (9.5 × 24.6 cm) Harry Ransom Center, Univ. of Texas, Austin

This photograph is a work of art that shows Girault’s two great loves: architecture — note the dual domes in the middle ground and a little ruin in the lower right — and botany: observe the magnificent cypress tree that cuts a diagonal through the entire composition and connects those two worlds, natural and built.

Stephen C. Pinson, the curator in the Met’s photography department, noted in the press conference that Girault saw intuitively something we all take for granted nowadays: how to see the world photographically. It’s hard to conceive how stunningly new this vision was in the 1840s: people saw, in his images, the first camel, the first person at the Wailing Wall, the first photograph of a Bedouin woman. Pinson observed that Girault’s contemporaries were experiencing innovations that compare with today’s experiments with virtual and augmented reality. He quite literally changed the way people saw the world — their own (see the the plant study below, from his garden in Paris) as well as strange, exotic lands that were previously unimagined.

One of my favorites in the show is Plant Study, Paris, 1841, a close-up in which Girault exhibits his obsession for plants: their textures, shapes, and the way they insinuate themselves into the built world, in this case against a stone wall. You can’t actually see the green on that veined leaf but it’s so realistically, and so vibrantly, presented in this daguerrotype that you can hold the color in your mind as you gaze at it.

Today the High Line, like every public space, is filled with “photographers” who reach into their pockets to pull out a little computer — it weighs less than a single bottle of mercury, whose vapors Girault used to develop his images — and shoot the striking array of architecture that lines both sides of the park: new and old, industrial and hi-tech, commercial and residential. Often we frame our shots with horticulture to show not only the juxtaposition of the built world with the natural one, but also the narrative of this place: how it emerged, from the railroad era via landscape architecture and horticulture, into a great public park.

The story of the High Line is as much a tale of photography — it was Joel Sternfeld’s powerful images that jump-started the restoration effort — as it is of adaptive reuse. It’s worth a trip to the Met to see where, and with whom, it all began. Below are a few random shots I pulled from my database that in some way owe a debt to Girault de Prangey. There are zillions more in the ten years of posts on this blog and my book, On the High Line. [As always, click an image to enlarge it.]