501 West 29th Street, standing defiant

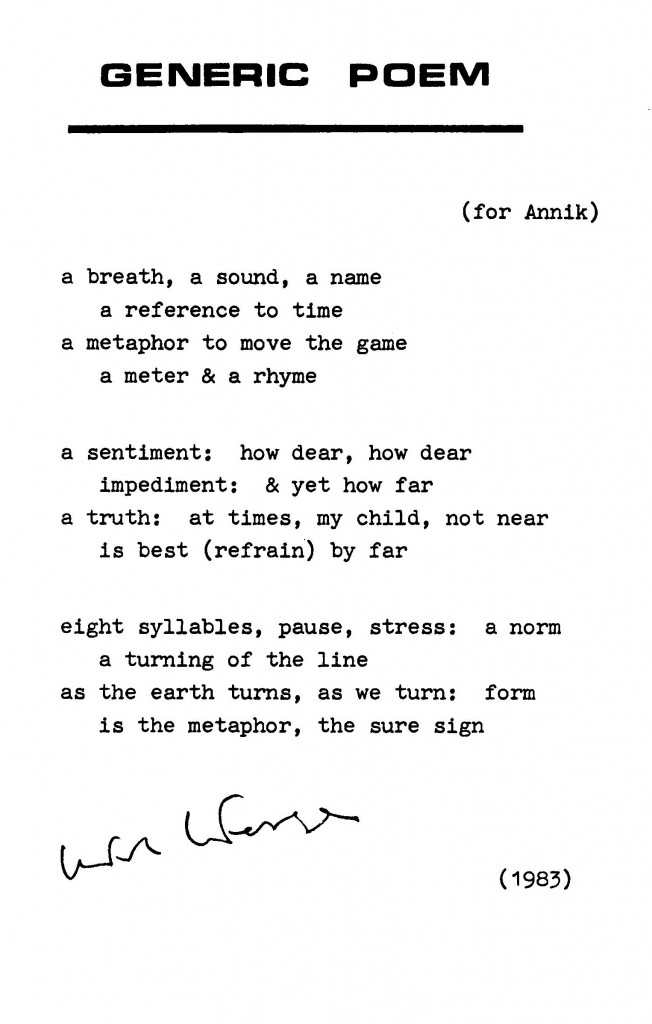

A couple of weeks ago my cousin Antoinette and I took a walk along the High Line. When we arrived at the construction scaffolding that now overstretches the park at 30th Street, I pulled out my phone and showed her the photograph above, which I had taken almost exactly a month earlier from the roof of the Ohm apartment tower on Eleventh Avenue. At the time I thought I was taking a photo of the green roof — now white with snow — atop the Morgan Mail Facility, one of my favorite buildings along the High Line. But when I got home and downloaded the picture I noticed something poignant and surprising that I hadn’t seen when I composed the shot on the windy rooftop: that former tenement at 501 West 29th Street, standing defiant and alone with a huge crane looming above its roof. When Antoinette and I arrived at this spot on December 7, the new construction had already reached beyond the second floor of tenement; it was storming past the north-facing windows of the dwelling’s inhabitants as it went.

A mixed-media artist who’s deeply fascinated by the role of fiction in art, Antoinette immediately thought of Roland Barthes and his book Camera Lucida. That tenement, she commented, is the element Barthes would have called “the punctum”: the detail that jumps out from the main subject of a photograph and surprises us. That tenement is what this photograph is really about: a group of Manhattan residents who apparently said Hell no, we won’t go, even as their windows disappeared and a concrete behemoth rose up beside them.

Below is a photo of 501 W. 29th Street that I took today from the High Line.

29th Street Tenement on December 17

When I got there, a light was on in the top-floor apartment, which is just hours away from being completely subsumed by the new construction. I found the scene heartbreaking, and what passed through my mind were Romeo’s last words in the crypt: “Eyes, look your last.” Maybe that seems overly dramatic, but my relationship to this place has always been something of a love story, so I’m going to let it stand.

Indeed, this is a dramatic moment in our neighborhood, though it’s by no means a unique one. I walked from stem to stern along the High Line today and counted 11 active construction projects in immediate proximity to the park, meaning I could land a baseball right in their middle of their work space.*

I try to take the long view about the extraordinary pace of change we are seeing in this area. (See here my response to Jeremiah Moss’ controversial piece in the New York Times about the High Line’s role in the changing landscape of West Chelsea.) But Barthes-like, my camera caught another truth hiding in plain sight: the huge advertising banner on the Morgan — the first in an apparent series — speaks to an irony that the residents of 501 West 29th Street surely know best of all. We are not sleeping easy here; on the contrary, this rampant change is what keeps many of us up at night.

I don’t know much about the history of 501 West 29th Street. I suspect that this structure, like so many other 19th century tenements along the waterfront, once housed the families of men who worked in the maritime trades: blacksmiths, ropemakers, riggers, haulers, carpenters. This area was, as Kevin Bone described in his excellent book The New York Waterfront: Evolution and Building Culture of the Port and Harbor, “a horizontal city of pier sheds and terminals, of railroad structures and industrial facilities…It was a gateway village between the metropolis and the sea. For many, this tidewater frontier town was the only New York they knew. It had its own hotels, bars, and brothels, as well as at least one floating church.” There were also iron works, foundries, lumberyards and factories in the blocks around 501 West 29th Street, and buildings like this are where the workers lived. There are still a few former tenements left along the High Line — including two on opposite sides of 17th Street and Tenth Avenue — but they are coming down fast. Some of these buildings have perfectly marvelous architectural details that one never really noticed from the street; today, from the High Line, we can all appreciate what was once a private architectural museum for train conductors of the New York Central Line.

In a 2010 forum about the High Line at CUNY’s Graduate Center the writer Malcolm Gladwell quoted someone who said that a great university is a place with “an engineered capacity for surprise.” This quality remains, for me, the enduring and abiding joy of the High Line. I visit the park almost every day, sometimes more than once; every time I go there I observe something I haven’t seen or noticed before. Every visit presents some sort of surprise, large or small. Today was no different, except I didn’t love what I was observing for the first time: the fact that you can now hear a constant thrum of construction from one end of the park to another. Even in a city this big, it seems unusual that you could walk for an entire mile and hear — uninterrupted — the sound of building: jackhammers, beeping tractors, scratchy voices emanating from distant walkie-talkies, whistles and toots, the sounds of men barking orders. Up and down the Line, from 30th Street to Gansevoort, this is the unabating soundtrack during business hours.

And yet: birds land on railings and tweet (the old-fashioned way). Babies cry, taxis honk, helicopter rotors whirl. The bells at General Theological Seminary call a community to worship. Yes, the city’s growth overwhelms us; it creeps past our windows and changes the way the light falls in our rooms, and therefore our lives. But as Gladwell also remarked in the CUNY talk, “this is the business we are in.” This is what we do in New York, and in all great cities: we engineer change. We can only hope that the surprises we encounter will be, for the most, meaningful or at least interesting.

In the meantime, get thee to the High Line and appreciate the views that are disappearing so fast.

501 West 20th, with a copy of “Love The One You’re With” near the front door

* Note: due to a recent a shoulder injury I’ve had to teach myself to throw lefty, so my range is about 75% of what it used to be, but I DO NOT throw like a girl. In my count I have not included the half-dozen projects that are clearly out of my range: those that are either east of Tenth Avenue, like the new Seminary condos, or closer to Eleventh Avenue, like the one near Edward Tufte’s gallery. But Derek Jeter could hit ’em! Also note: I’m not counting sites that have been cleared and are ready for construction, only those where there are men at work. I counted the Whitney Museum and the new headquarters for Friends of the High Line as two separate projects.