Derailed by the death of my mother and a few work projects, I took my eye off this blog for awhile, and have only now begun the process of revising a few pieces that fell out of date. First: the “What’s That Building?” guide. I’ve updated this feature to include many new buildings that have popped up around the High Line in the past couple of years, and also re-formatted it so the photos are larger. In the process of updating I removed the “glimpses of architecture” we can see in the distance — towers, spires, domes — and created a separate page that identifies them; it too is (roughly) organized from south to north. “What’s That Building?” is the most trafficked piece on the site, so I’m happy to have it back in good shape. Thanks to the readers who wrote and gently nudged me.

Writing about new buildings in my neighborhood is tricky because the presence of so much heavy construction is extremely hard on the nerves. I find myself hitting the delete key more often than usual in an effort to maintain composure and objectivity. There are several large projects on my block alone, and we must endure the noise, dirt, blocked traffic and fumes from idling vehicles all day and also (incredibly) late into the night. Developers in this town have so much power and influence that they are able to routinely get permission to work long hours; in our case, work begins at 7am and continues until 11pm, six days a week. And we are lucky; the developer (Albanese in partnership with Vornado) has been extremely responsive to complaints and requests from residents, and the crews are polite and highly focused on worker and pedestrian safety. But there’s only so much they can do. Modern construction requires gigantic machines, sky-piercing cranes, massive flatbed trucks, endless parades of cement mixers, and brutally intrusive, never-extinguished LED klieg lights that cast a creepy, bone-white glow in bedrooms across the street and down the block.

It can feel sometimes that no one cares about the actual people who live on these blocks that are being re-made all over the city. My downstairs neighbor has a small child whose bedroom window looks out on the construction project. Who cares about the late-night disruption to a toddler? Does the Mayor? The Buildings Dept.? The developer? The truck driver? Probably not; their interests are to make the city (and their pocketbooks) hum, one way or another. And so the rest of us suffer through it, doing our best to be good citizens who somehow see, and celebrate, the benefits of all this “progress.” It would be so much easier to accept if at least half of all this new construction were devoted to affordable housing. We would still suffer the long, ugly barrage of construction, but at least, at the end of it, our neighborhoods would retain the diversity that drew most of us here in the first place. But that is a subject for another post.

For my part, I take comfort in the originality, diversity and — occasionally — drop-dead beauty of the architecture that continues to noisily rise around me, disrupting my inner peace and that of my treasured neighbors. A few months ago a friend and I hiked north to to see The Inkwell, a former public school on West 45th Street, built in 1905, that has been transformed into a small condominium with eighteen residences. The designers have done a splendid job evoking the history of this place; it’s a great example of adaptive reuse in a residential project. But the neighborhood around it is filling up (and has been for many years) with dreary, glass skyscrapers. Hell’s Kitchen has also been gentrifying fast, but in a much less interesting way (with the glorious exception of Bjarke Ingels’ Tetrahedron on the West Side Highway). We have round-the-clock noise and disruption in West Chelsea, but we also have buildings by Frank Gehry, Renzo Piano, Cary Tamarkin, Annabelle Selldorf, Jean Nouvel, Norman Foster, Shiguru Ban, Zaha Hadid, and Neil Denari.

The designers of the High Line — its architects, landscape architects and staff of the founding Friends group — made every effort to preserve the history of the freight railroad in the physical design of the park they created. I’ve written about this extensively here and in my book, and the examples are numerous, from the preservation of the original railroad tracks and the mix of indigenous and non-native plants that were reintroduced in the various gardens to the re-telling of the story of the West Side Cowboy, making it the fundamental part of the High Line’s creation story. This connection to the past inhabits the entire park, from one end to the other, and despite the recent controversy about whether or not the High Line is “a failure” because it became over-crowded and the neighborhood over-gentrified (also a subject for another post) it is indisputable that founders’ design philosophy is a fundamental part of the park’s success.

Alongside the High Line, as developers madly build out their empires, bits of history can be discovered in the new construction. I’ve found that little observations can calm and delight an agitated mind, so here’s one example for those of you who are also feeling overwhelmed and saddened by the tsunami of change in our patch.

As construction was just beginning at 510 W. 22nd Street, I noticed some odd, round wooden forms on the top floor of a portion of the structure that hadn’t been torn down. I took a photo and filed it away. Last week I was passing by and stopped to have a good look at what will be the lobby of this CookFox-designed office building, and figured out what those forms are for: they are used by the (incredibly annoying) cement pour-ers to create “mushroom columns,” the very same weight-bearing structures that Cass Gilbert used in the R.C. Williams warehouse (the link goes to my High Line Architecture article) and Cory & Cory et al used in the Starrett-Lehigh Building a few blocks north.

Here’s a crummy shot but you can see the columns (and the hugely irritating LED lights that are invading our homes…)

Below are photos of the R.C.Williams warehouse (now Avenues School), taken by Anthony W. Robins, an historian and expert on Art Deco architecture who wrote the building’s nominating essay for the National Register of Historic Places (and also a terrific book about Grand Central Terminal).

Mushroom column, low floor. Photo by Anthony W. Robins

Note that the columns get skinnier on the higher floors:

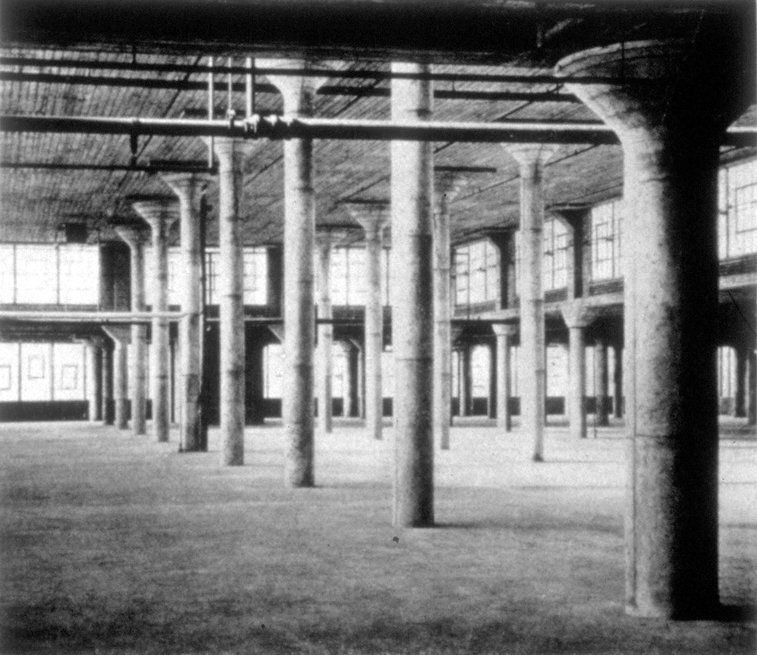

Mushroom columns, higher floor, R.C. Williams warehouse. Photo by Anthony W. Robins

And this is an interior photo from the Starrett-Lehigh Building, which also shows this old railroad warehouse’s distinctive windows:

It’s a small consolation amid the daily, eighteen hour onslaught of noise, fumes, dust, light and congestion. But to see the architectural history of the industrial period of this area recalled in a new office building does give me joy. It makes the disruption…

almost worth it.

Outstanding !!!! (not a bit snarkey)