An old friend recently wrote a piece on her blog about the place she goes when she wakes up in the middle of the night and can’t get back to sleep: childhood books. Whether it’s Anne of Green Gables, The Borrowers, Pippi, Harriet, Reepicheep, Lad a Dog, Lightfoot the Deer or Whitefoot the Woodmouse, this retreat into a long ago chapter is an engine of escape, the tool that can finally quiet a restless, adult mind.

I was thinking of Beka’s piece when I opened up the new book Dronescapes and found this image of the place where I go in those quiet hours when I can’t, for whatever reason, sleep:

It’s Keyhole Arch at Pfeiffer Beach in Big Sur, shot using a drone by Romeo Durscher. It was taken during the Winter Solstice when the sun cuts a particular angle and shines through what looks like a carved doorway in the giant rock just off the shoreline. I’ve photographed this magical spot hundreds of times over the past 20 years, but never during the Solistice. Durscher’s photo has a shamanistic, almost mystical quality, since it captures the figures on the beach in the waning rays of sun as well as the shadows outside them. Is it possible to get such a photo without a drone? Yes, you can clamber up a steep, sandy hill and hope for the best. But there’s something about a drone…

These days, as Dronescapes shows, the size of cameras has shrunk while chip capacity has grown, and suddenly, in the past couple of years, a new form of aerial photography is emerging. But in a weird twist, increased government regulation of drones means that the possibilities are increasing and contracting at the same time. It’s both an exciting and frustrating moment, because the technology is there and prices have come down drastically, but those shots you want to get — of bridges, monuments, cityscapes — are increasingly off limits. Dronescapes is the first coffee table book to give us a look at the state of the art.

Many of the photos are striking mainly because of the perspective they offer. I’ve written about this before in regard to the High Line: the thing that was, at first, so stunning about this place was the fact that there are you, strolling through and over the city streets at a consistent height of 30′. I’ve lived in Manhattan my entire life and spent plenty of time on the second floor of buildings (including living in one for five years) but nothing matches the experience of perambulating outdoors for a mile or so above ground. So anyone who’s been on the High Line will know exactly what I mean; perspective can be everything.

Here’s another familiar but totally unfamiliar sight:

This is the iconic Christ the Redeemer in Rio de Janeiro, shot by photographer Alexandre Salem at an altitude of just over 23′.

Closer to home we find this old friend…

Drones have the capacity to make familiar images surprising; here, in one of the most photographed icons in the world, it’s the shape of the pedestal, which mirrors Lady Liberty’s crown but is something you can’t appreciate from the perspective most of us get from below. (Of course, tons of people see it everyday from airplanes bound for or leaving Newark Airport.)

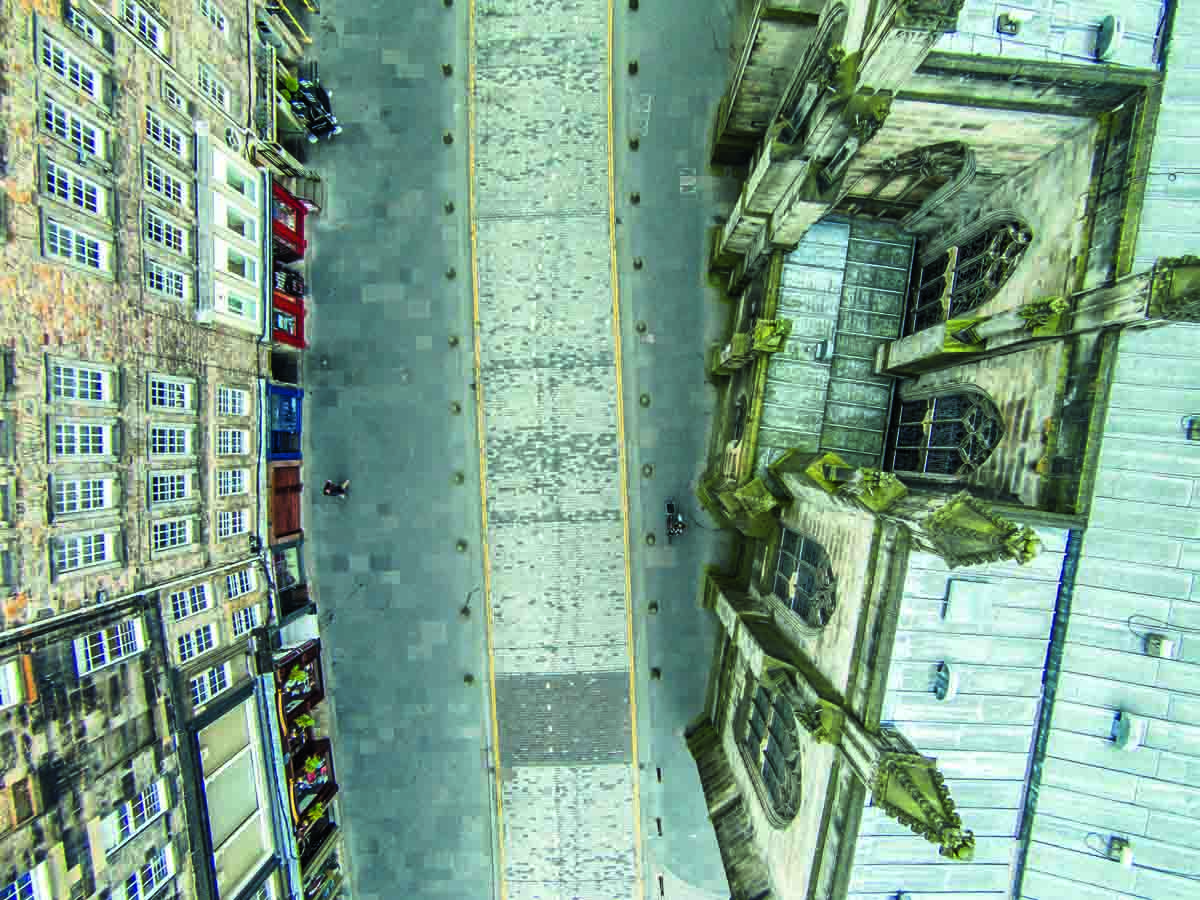

My favorite images in Dronescapes are the ones that show patterns in the landscape; these are the photos that come closest to being art, and which delight the eyes by offering a new and fresh view. Like this photo, taken in Edinburgh, Scotland by Francesco Gernone.

I was talking about this book with my friend Ben Schott, a professional photographer before he became a writer, and he mentioned a famous observation made by Robert Capa, co-founder of Magnum: “If your photographs aren’t good enough, you’re not close enough.” It’s an interesting thought that applies to the modern drone photographer as well as the rest of us down below taking hand-held shots, because Capa was talking more about engagement than actual distance. It’s about what you see, not how close or far away you are from the subject. Could anyone else have captured what you saw? If not, chances are it’s a pretty great shot. (Or, if I may, Schott.)

Dronescapes is a first draft of history in the new art of aerial photography, and as time goes by (if the regulations don’t kills us) what surprises us won’t be so much the perspective as the artful composition joined with the particular moment — never to be repeated — that the photographer stumbled upon. There aren’t enough of these in in the book, but this one is a winner:

You can also check out Dronestagram for more photos. Dronescapes: The New Aerial Photography from Dronestagram is a beautifully designed book, published by Thames & Hudson and edited by Ayperi Karabuda Ecer. There are no shots of the High Line, but in 2014 AnimalNewYork flew a drone over the section at the Rail Yards which was then being built. It was a thrill to get a peek at the progress, and it was a perspective that, at the time, only a drone could manage. If it was legal then, it sure isn’t now.

Here, just for the fun of it, is a photo of mine from the old days of film, of Keyhole Arch at Pfeiffer Beach in Big Sur.

Hey Niks, Thank you for the shout out and this is incredible! These shots are so beautiful and the opening one looks like something out of Lord of the Rings. I have been to that beach (on your suggestion, actually) and I am amazed by this. I think we should try to go once on the solstice–one for the bucket list? Great posting, these pictures are incredible. xo

yes and yes and yes!