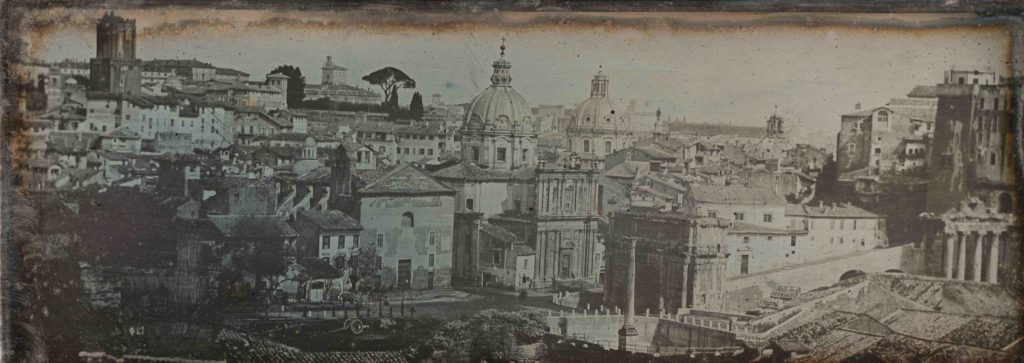

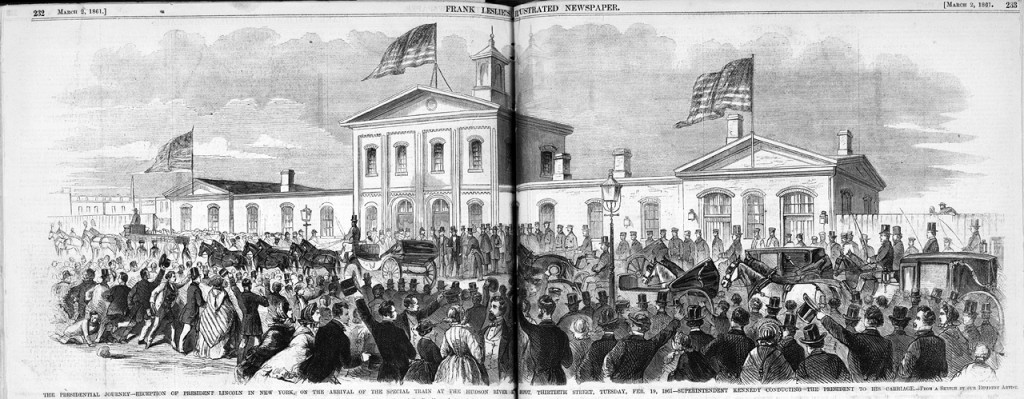

Abraham Lincoln’s Special Inaugural Train at the Hudson River Railroad Depot, 1861. From Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, courtesy Library of Congress

Tomorrow the Tenth Avenue Spur opens, marking the completion of the High Line after twenty years of labor and love. There will be much to say about this new space once the public is welcome, but first, perhaps, let’s linger on the past, and the original purpose of this steel bridge that crosses Tenth Avenue into what is today one of the largest mail sorting facilities in the country. The history goes all the way back to the 1860s, when a train station owned and operated by the Hudson River Railroad stood on this ground. Its very first passenger was Abraham Lincoln, who passed through on February 19, 1861, en route to his inauguration in Washington, D.C. That hopeful, optimistic moment was captured in the illustration above, which appeared in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. It shows the depot in the background and President-elect Lincoln being escorted to his carriage by the superintendent of the Metropolitan Police. What’s so haunting about this story — and this spot along the High Line — is that four years later, on April 25, 1865, Lincoln’s funeral train passed through the depot on its westward journey to Springfield, Ill.

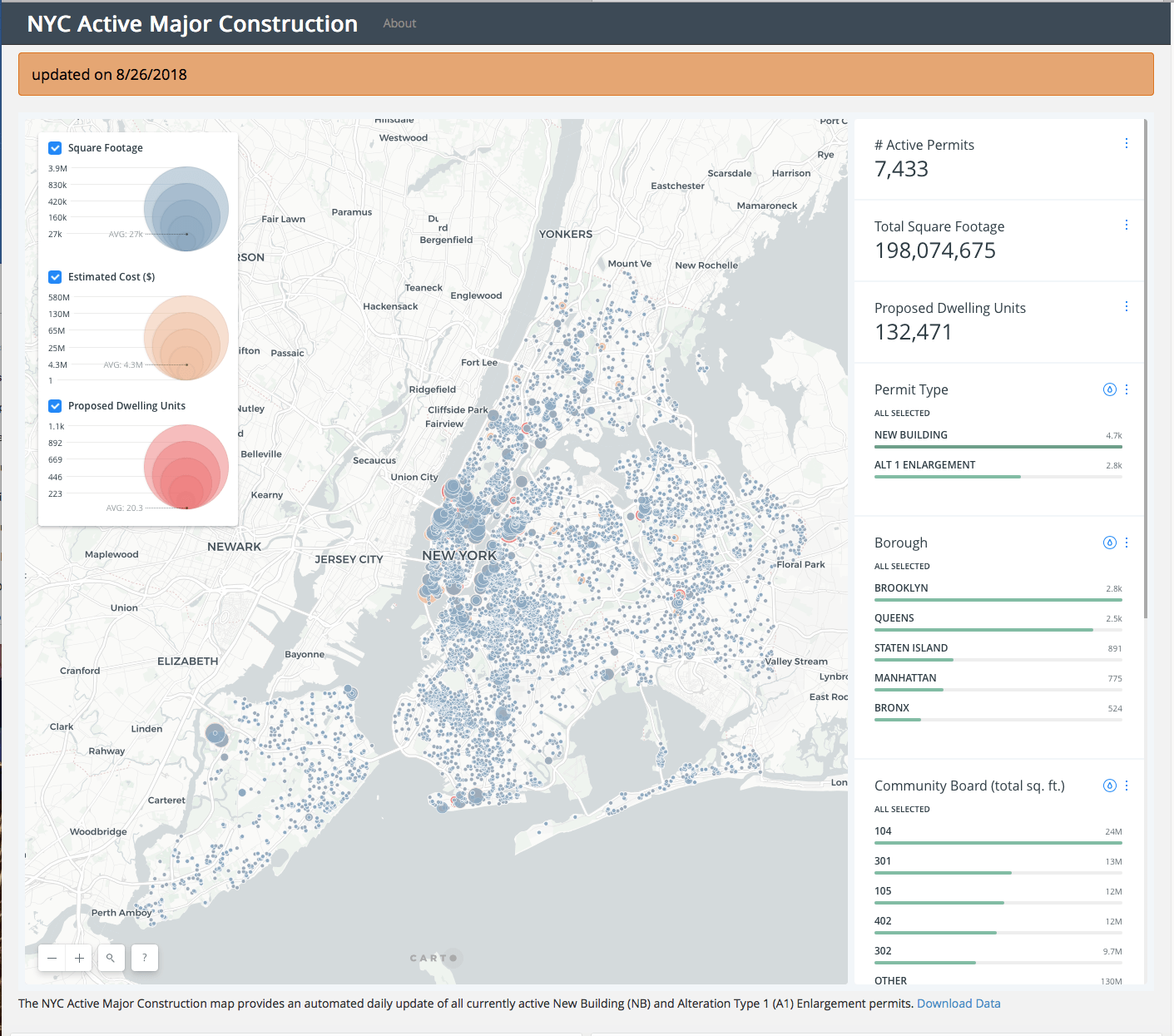

Now towering above this hallowed ground is the Morgan General Mail Facility, completed in 1933 with funds and labor from the New Deal’s WPA program. It was designed to carry the parcels and letters of some 8,000 mail trains that crossed the country each year on an intricate network of rail lines, before they arrived at this destination on 30th Street and Tenth Avenue. This aerial photograph from 2012 shows the passageway, now blocked up, in the north corner of the massive structure, which was once used by the mail trains to enter the building:

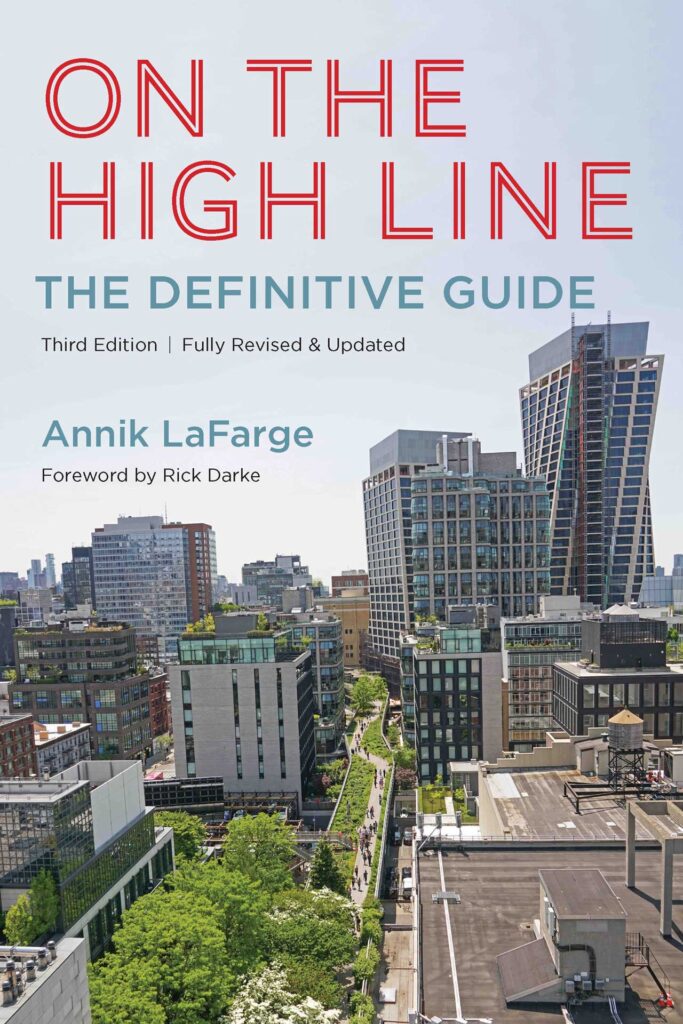

My photo also captures another unique element of this facility: its enormous green roof — one of the largest in the United States. For photos taken on the roof (including a jolly family of Canada geese who passed through during the period I was photographing) see my longer piece about the Morgan, part of the High Line Architecture series on this blog. The High Line is, of course, one long, linear, green roof — and it’ll be just a bit longer as of tomorrow, when the new section opens. The Morgan’s roof is not accessible to the public, but you’ll find lots of photos here, including a special little plant — the Tragopogon dubious, aka yellow salsify, that hitchhiked its way on a puff of wind from the High Line up to the Morgan, cross-pollinating its sister roof and creating a horticultural connection between these two important landmarks of American history and culture.

So the story of the High Line continues.