The second building in my new series about architecture along the High Line is the former R.C. Williams warehouse, now Avenues School, on Tenth Avenue between 25th – 26th Streets. [Click here to read the first piece in the series, about the Westyard Distribution Center, and here for the “What’s the Building?” feature]

Just before Avenues opened last Fall I gave a lecture in the school’s cafeteria to the teachers and administrative staff. I wanted to welcome them to the neighborhood and also share some insight into the unique role their building plays in the High Line’s history. While researching the lecture I discovered a short book in the New York Public Library about R.C. Williams, the company that built this warehouse in the early 1930s. In its pages, to my great delight, I found a surprising story that makes a direct thematic link with the schoolhouse of today.

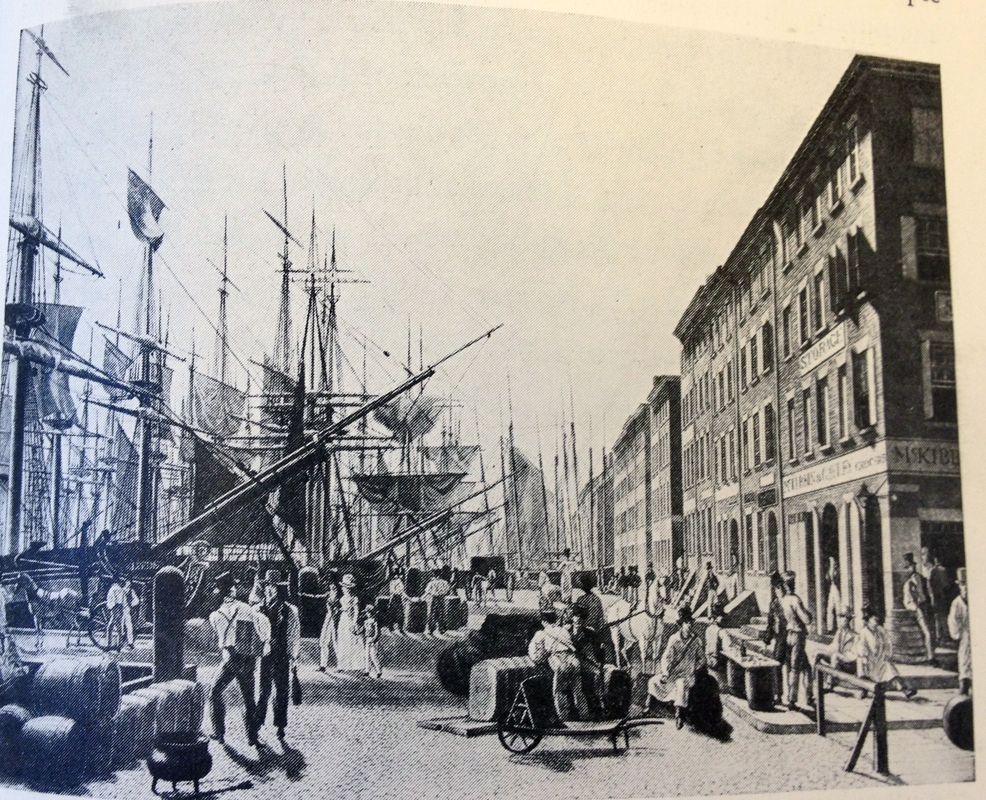

The story begins in the first decade of the 19th century when New York City had “four banks, no water supply worth mentioning, no gas, nor any of the conveniences we find so necessary today.” It did, however, have “the finest harbor on the Atlantic Coast,” and it was here, in 1807, that Robert Fulton launched the first commercial steamship and sparked a revolution in trade and commerce. At the same time, near the dock where Fulton’s vessel departed, another young entrepreneur, Cornelius Vanderbilt, was beginning to build his shipping empire. And two ambitious young men, Richard Williams and John Mott, partnered in a wholesale grocery venture that would use the modern transportation technology to forge new markets across the ocean. Like Vanderbilt, they established themselves on South Street, the red hot center of international trade. Mott & Williams became stockholder’s in Fulton’s Ferry, and located their store as near to it as they could. From their front door the two young grocers could look out and see “a forest of masts of vessels from all the ports of the world.”

R.C. Williams was one of America’s first truly global companies, the original “supermarket to the world.” Looking back on its first few years, the author of a company history published in 1933 observes that:

“Our pride in the year 1811 was our fleet of tall clippers, our lines of packet ships, which sailed out of New York, Boston, and Charleston to all the oceans. In the tea races to China they defeated the fastest vessels of the British, the French and the Dutch. We were in many ways sovereign of the seas. Our ships carried furs, whale oil and West Indian rum and spices to Europe, returning loaded with finery, food delicacies and well-wrought articles of continental workmanship.”

During the course of its long history, R.C. Williams was constantly innovating. It was among the first to distribute food in cans, and pioneered in packaging, marketing, merchandising and retailing. They were also trendspotters, and predicted — to their enormous profit — that coffee would become king in the American home and Prohibition would be short-lived. They created one of the first international brands, Royal Scarlet, which they then franchised across a series of retail store locations. Today we see this everywhere, from Whole Foods to small regional chains; R.C. Williams was doing it back in the opening years of the 20th century.

But beyond its global reach and innovation, what I found most fascinating of all is that this company, from its very beginnings, pioneered in ideas. They saw themselves “as a medium of exchange, not only of commodities but of information and ideas.” They offered advice to customers on everything from bookkeeping to window dressing, and trained their buyers so they could advise customers on crop conditions around the world, seed production, sanitation, managing overheads, doing business in international markets, and more. Not only was this company an innovator in the food business; it was, almost a century before the age of the Internet, an information company.

Over the decades R.C. Williams moved and expanded its business, and in the 1920s learned of yet another transportation innovation that was on the horizon: Robert Moses’ High Line. This elevated freight rail line promised another revolution in New York City trade and commerce: it would cut through existing buildings and enable locomotives to sail above the congested city streets, their box cars filled with every conceivable type of freight, from perishable goods like meat, dairy and vegetables to books, furniture, cigarettes and the U.S. Mail.

And so, a century after its founding, the R.C. Williams Company again put itself at the crossroads of the latest transportation innovation, and purchased land on Tenth Avenue for a new warehouse. They hired Cass Gilbert, one of the greatest architects of the day, to design a building that would be worthy of their position in the global food industry they had helped develop. Gilbert, architect of the U.S. Customs House and Woolworth Building, modeled the new warehouse after his Brooklyn Army Terminal, which had recently been completed. He designed it to maximize efficiency and create a seamless flow of goods from the tracks of the High Line, into the warehouse, and onto the many trucks that waited on loading docks in the street below.

On August 1, 1933 — a year before the High Line officially opened — a train rumbled down the viaduct to commemorate a moment in history. Someone snapped a photo, and in it we can see an extraordinary convergence of people, industry, and the entrepreneurial spirit that has long driven this city. There, on the loading dock of his new warehouse, stands Arthur P. Williams, a direct descendent of the founder of this global enterprise. He is shaking hands with Frederick Ely Williamson, the man now running the New York Central Railroad, the line Cornelius Vanderbilt built off the profits of his shipping interests — a business begun, like the R.C. Williams Company, a few miles downtown near South Street around 120 years before. Perhaps Vanderbilt had even known, and done business with, the original Mr. Williams. It’s certainly possible.

What drew me to dig deeper into this history is Avenues, which calls itself “the World School” and developed from a vision to create a “truly global education.” Having just completed its first academic year, Avenues is in the process of building campuses in Sao Paolo, Beijing and London. Eventually, its students will engage in the classroom live, via teleconference, with young people from other cultures around the world. The project has attracted controversy, but it’s a bold new experiment in education, and I think it’s notable that it takes root on a patch of Manhattan real estate that is rich with a history of innovation.

In 1931 Cass Gilbert accepted the Gold Medal for Architecture from the Society of Arts and Sciences, and put forth his own vision for the future. It’s one that would echo well in the halls of the building he was then designing:

“My plea is for beauty and sincerity, for the solution of our own problems in the spirit of our own age illuminated by the light of the past; to carry on, to shape new thoughts, new hopes, and new desires in new forms of beauty as we may and can; but to disregard nothing of the past that may guide us in doing so…”

There’s a spirit that abides in this building. It has been gorgeously restored and transformed into a 21st century school, but the loading dock is still there, just outside the cafeteria, and the train tracks are too. You can see them all from the High Line. On the roof flies an American flag, but it too has been altered for a new age: the artist, Frank Benson, digitally mutated the perspective of the stars and stripes in an effort to create a flag that appears to be perpetually waving in the wind. Check it out: it looks familiar, but it has the future written all over it.

[Click here to read the first piece in the High Line Architecture series, about the Westyard Distribution Center, and here to see all the pieces in the series]