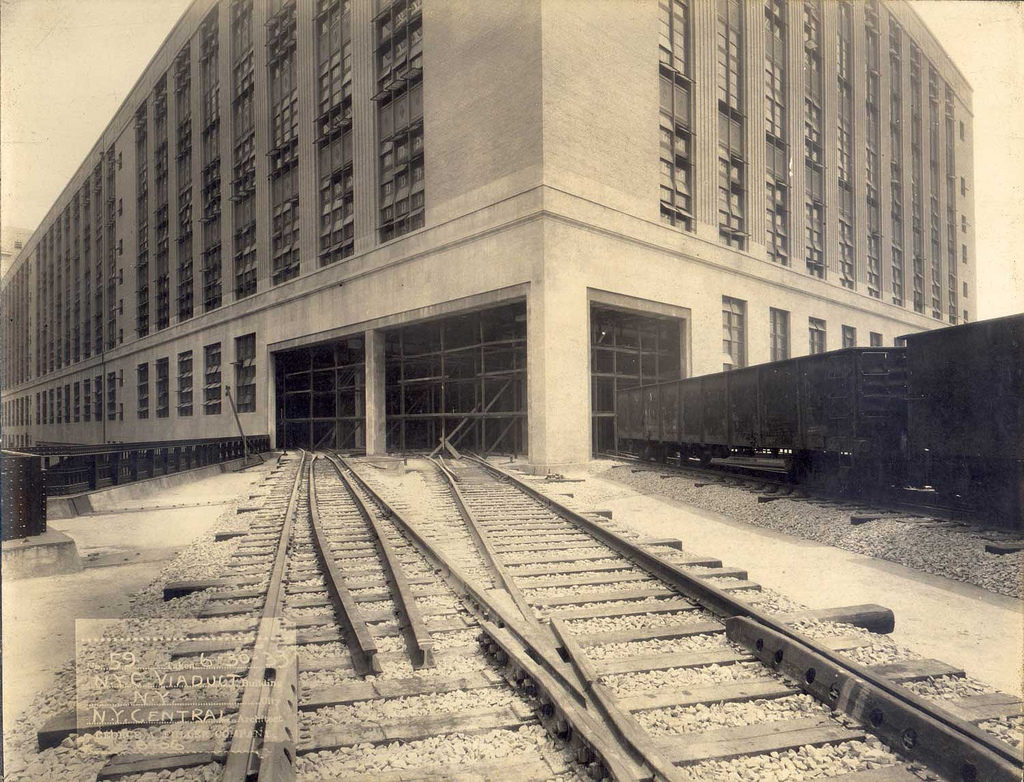

After years of searching, finally I’ve located a photograph of the Hudson River Railroad’s Thirtieth Street Depot. This is the station that once occupied part of the area where the Morgan General Mail Facility now stands on Tenth Avenue. It’s the train station that received, as its very first passenger, President-elect Abraham Lincoln, who passed through on February 19, 1861 en route to Washington, DC for his inauguration. I post here a photograph taken in April 1902, looking West down 30th Street:

The NY Central & Hudson River Railroad 30th Street Station, April 6, 1902, looking West. The New-York Historical Society, used with permission.

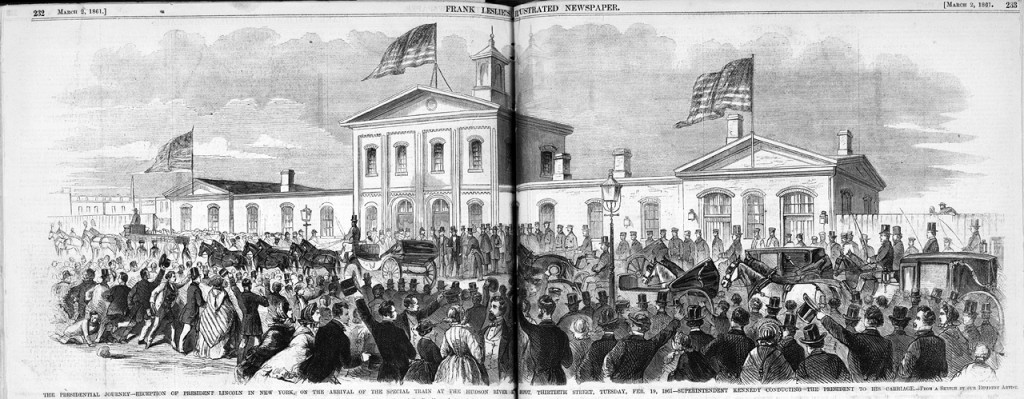

It’s a bit less grand than the illustration I’ve been relying on to tell the story of this spot, made by an artist for Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper after Lincoln’s visit:

Abraham Lincoln’s Special Inaugural Train at the Hudson River Railroad Depot, 1861. From Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, courtesy the Library of Congress

It was also here that, four years later, President Lincoln’s body was transferred to a funeral train headed north on the Hudson River Railroad, after the cortège had reached New York on another railroad line. The Hudson River Railroad was designed to link New York with Albany, and from there connect with other roads heading west across the country. At 144 miles in length, the line opened in October of 1851, and while it took a good five hours to travel from Manhattan to Albany, the new railroad beat the fastest steamships by at least two hours.

Those interested in a detailed account of the obsequies and “Sombre Grandeur of the Funeral Pageant” will find a long, moving series of articles in the New York Times issue dated April 26, 1865, beginning with the “dense masses of immovable people” who turned out at City Hall to file by the President’s corpse and pay their respects. His body had reached New York at noon on Monday, April 24th, and lay in state at City Hall until Wednesday the 26th. At 12:30 on that day the funeral car arrived at the Hall, drawn by sixteen “magnificent gray horses, led each by a colored groom.” After what the Times reporter called “a vexatious delay,” a bugle sounded and the funeral procession — with countless regiments from every part of the military, an Invalid Corps and a battalion of police officers — finally made its way up Broadway toward the railroad depot at Thirtieth Street. Joining the procession was Bruno, who came to be known as “the dog mourner.” He was a large Saint Bernard who bolted from his owner, Edward H. Mostly, just as the funeral car passed the corner of Broadway and Chambers Streets, and followed along underneath the coffin for many blocks. “By what instinct was this?” the reporter asked, and then provided the answer: “Bruno was a friend and acquaintance of Mr. Lincoln’s, and had passed some time with him only a few days before his death.”

At 2:30 an aide “came galloping down Ninth Avenue” to report that the cortège was approaching. Shortly thereafter, and to “the thrilling roll of drums, the clash and swell of music, and the quick, sharp sound of the ‘present arms,'” the procession reached the station. Inside the depot was “a knot of wounded soldiers…[who] sat, poor fellows, fighting their battles over again.” Lincoln’s catafalque was transferred to the Union, a “splendid locomotive” that had conveyed the President-elect four years earlier on his triumphal progress from Springfield to Washington for his inauguration. It was now draped in funerary cloth, its lamp decorated “with a magnificent wreath of living flowers.” Inside the funeral car Lincoln’s body was accompanied by that of his young son, Willie, who had died in February of 1862.

A bell rang, the conductor called out “All aboard!” and at 4:15 pm the Union pulled out of the Thirtieth Street Depot. Mourners were lined all along Tenth Avenue; they removed their hats as the funeral train emerged from the gate, and then disappeared around a curve.

Today, standing sentry over this hallowed ground, is “Brick House,” a 16′ high bronze sculpture by Simone Leigh. In an interview with Calvin Tomkins of the New Yorker, Leigh explained that the title of her work refers, in part, to an expression in Black culture. “If I called someone a brick house,” she said, “any Black person would know what I was talking about. It’s a woman who’s — I hesitate to use the word ‘strong,’ because of the stereotypes of Black women as towers of strength. It’s about the ideal woman, who is fragile.” It was the first monumental sculpture in Leigh’s Anatomy of Architecture series and, according to Friends of the High Line, “encompasses several architectural and cultural references in tribute to the strength of Black female beauty.”

Simone Leigh, “Brick House” on the Tenth Avenue Spur

Read more about the Morgan General Mail Facility

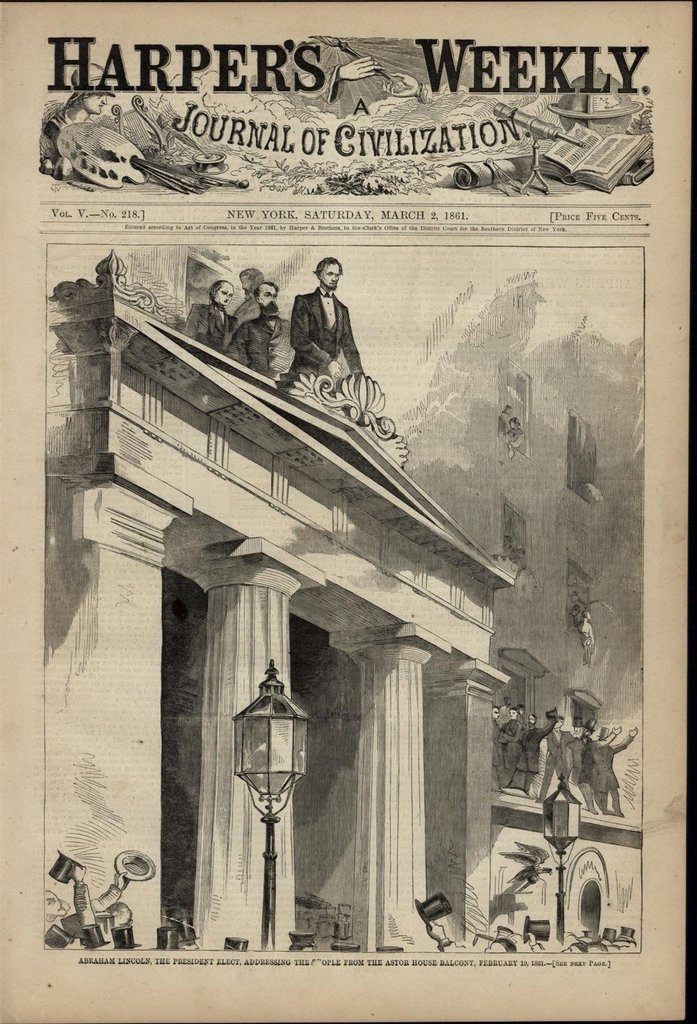

Read more about President Lincoln’s Dangerous Day in Manhattan, 1861

SOURCES

The Rise of New York Port: 1815-1860, by Robert Greenhalgh Albion

The New York Times, April 26, 1865, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1865/04/26/88155015.html?zoom=15.36

Christopher Gray, “Where Lincoln Tossed and Turned,” The New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/27/realestate/27scapesready.html