Tim Saternow, Furniture Exchange Warehouse, 525 West 22nd Street, 1940 (Spears Building), 2010 Watercolor on paper, 60×40”

The fourth entry in the High Line Architecture series is the Spears Building at 525 West 22nd Street.

Once a furniture warehouse operated by Spear & Co., this sprawling, handsome brick building was constructed in 1880 by Kinney Brothers and used as a cigarette packing factory. Kinney was a unit of the giant American Tobacco Company, and until it was broken up by antitrust laws it controlled more than 90% of the tobacco market in the USA. Kinney had a large operation on 22nd Street, capable of putting out 18,000,000 cigarettes each week. 600 people worked in the factory complex, which consisted of several other buildings on the block.

In 1892 a five-alarm fire gutted the entire factory, destroying tens of millions cigarettes. Thankfully the fire started early in the morning and no one was injured, but damage was extensive. This sad event prompted one of my all-time favorite New York Times headlines, which ran on October 7, 1892: “One Fiend Beats Another: Fire Smokes Forty Million Cigarettes in Short Order.” Imagine that: the smoke from 40 million cigarettes burning just above the lawn on today’s High Line….

By the time Robert Moses was envisioning an elevated freight railroad in the 1920s, the warehouse had been taken over by Spear & Co., and instead of cigarettes it was filled with furniture. In 1931 a section of the complex on the east-facing side was torn down to accommodate the High Line. Tim Saternow’s marvelous painting (above) captures the street scene of the 1940s, including the old street lamps and iconic water towers that still sit atop the building.

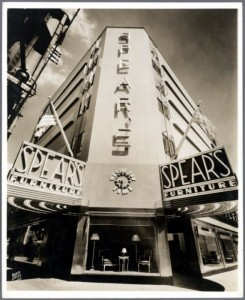

Like the R.C. Williams wholesale grocer a few blocks to the north, Spear & Co. installed loading docks along the side of its warehouse so trains could expeditiously load furniture onto box cars for distribution around the country. (Today, the stadium-style “seating steps” of the High Line cover the area where the rail sidings were.) Spear & Co.’s headquarters were in Pittsburgh and they operated several retail stores in Manhattan, including a large one on 34th Street next to the Empire State Building, one in Brooklyn, and the cool Art Deco building that appears in the photo below on Jamaica Avenue in Queens. The company motto, “We give you time,” appeared prominently on its storefronts; on the Queens store, it wraps around the clock on the building’s facade just below the company name. [For more about the Spears furniture business see this excellent article in Brownstoner.]

Saternow’s painting depicts a familiar scene on the industrial West Side during the early decades of the 20th century: the mix of rail and trucks that moved goods around the city and the country. In an odd coincidence, the general manager of Spear & Co., Arthur S. Guggenheim, died on a train en route from his home in Pittsburgh to Penn Station; it was the same year that Tim Saternow’s painting depicts: 1940.

The b&w photo below was taken in 1934 from the newly opened freight viaduct, looking north from 21st Street. It shows the Spear & Co. warehouse on the left, and the Guardian Angel School (right foreground) which was originally located on 23rd Street. The New York Central Railroad paid the church to move to its current location, on Tenth Avenue and 21st Street, since it was blocking the path of the viaduct — a reminder that this neighborhood has always been a work-in-progress.

Spear & Company furniture warehouse, from the High Line at 21st Street, 1934. Courtesy West Side Improvement Project brochure

After the last train ran along the High Line in 1980 the viaduct was abandoned, and over time transformed into an invisible (at least from the street) spontaneous garden. Rick Darke’s photo (below) shows an intriguing little path made by trespassers — precursor to the more popular one that would replace it some three decades later — plus a few birds sitting like notes on a musical staff, looking down on a peaceful wild garden in the middle of the city.

The photo below shows the abandoned loading dock along with a multitude of graffiti that once covered the building. The NYC graffiti police removed most of the graffiti from the High Line during remediation, but on the Spears Building they left the famous REVS COST tag along with faded remnants of a few others. Running down the southeast corner of the building (far left in the photo below), you can also see the faded letters that spell out TOWER’S, the apparent successor to Spear. Tower operated bonded warehouses in locations throughout the city, including along the west side of Manhattan; according to one source the company operated a warehouse at 511 W. 22nd Street building, which was once part of Spear’s factory complex, between 1955 – 1971. These ghost signs are common around West Chelsea; just a bit west, at 532 W. 22nd, are the faded letters of a long-gone lumber company. But as development rampages through the neighborhood they are disappearing fast. New construction begun in 2017 will most likely block the lumber ghost sign within a year or two.

The Spear & Co. factory was converted into a condominium in 1996, and while many unit owners renovated away the details of the building’s industrial past, some of the lofts retain the original wooden plank ceilings, iron castings, and support beams that recall the old factory. Long ago, some worker hammered a series of nails into a pattern displaying the initials “F.A.,” which are now part of a loft on the 5th floor. Was he a cigarette packer or a furniture maker? No one knows.

In 2012, when Section Two of the High Line opened, the Spears Building became the backdrop for the “seating steps,” a popular hang-out for people-watching, snacking, smooching, and the occasional wedding ceremony. The High Line Art program uses the wall of the building just opposite the seats to project films or display art works, like Ed Ruscha’s mural in 2014. So this place has also become an outdoor auditorium/art gallery as well.

Almost exactly 120 years after the devastating fire of October 1892, the Spears Building was hit by another fiend: Hurricane Sandy. The “superstorm” ravaged New York City On October 29 during a full moon, when tides are at their highest. Worse, the storm surged coincided with the approaching high tide along the Atlantic Coast. The Hudson River, a tidal estuary, rose a record 8 to 9 feet in Lower New York Bay, and on 22nd Street the river exceeded the 4′ level, flooding the basement and lobby of the Spears Building. The photo below was taken by Haider Gillani during the storm; click here to see a photo from the same place taken in July 2014 and here to see the Sandy high water mark emblazoned (still) on 22nd Street.

22nd Street, outside the front door of the Spears Bldg., during Hurricane Sandy. Photo by Haider Gillani.

Tim Saternow’s painting, which he graciously allowed me to use here, has been hanging in the Spears lobby since 2009 — the same year the High Line opened — and it’s a much-loved fixture by the building’s residents. It was almost a casualty of the hurricane, but luckily the water didn’t rise quite high enough to reach it. Tim was able to rescue the painting the day after the storm, and once the lobby had been repaired it was returned to its rightful place.

The other distinctive element of the Spears Building is the pair of “silent sentries” that have stood on its roof for more than a century. New York City is filled with water tanks, what beloved CBS newsman Charles Kuralt described as “the hoops and staves of the Middle Ages.” As our neighborhood reinvents itself with modern architecture and 21st century urban greenways made from post-industrial ruins, the water towers on the old cigarette-packing-factory-turned-furniture-warehouse-turned-condominium are like anchors of the past. They help us better appreciate the long — and ongoing narrative — of this wonderful place. Here are some photos I’ve taken over the years in different seasons:

Note: special thanks to Livin’ The High Line readers Bruce Ryan and Susan Spear for their feedback and insights.

Morgan General Mail Facility – Tenth Avenue between 28th – 30th Streets

Westyard Distribution Center – Tenth Avenue between 31st – 33rd Streets

R.C. Williams Warehouse / Avenues School – Tenth Avenue between 25th – 26th Streets

Spears Building – 525 West 22nd Street