For Johnny.

The genius of the High Line at the Rail Yards is that it’s two different places at once, yet each part perfectly captures the essence of this now mile-and-a-half long, exquisitely beautiful park. [As always, click an image to enlarge it.]

Every landscape tells a story, whether its urban, rural, or wilderness, and much of what I’ve been doing on this blog for the past five years is peel back the layers of this particular place to discover the many threads in a rich, ongoing narrative about the Far West Side of our little island. What makes a visit to the final section of the High Line so exciting is that its creators have taken the old story of the abandoned railroad and married it so seamlessly and artfully with the new story of the High Line Park.

A simple change in paving material and a gate that closes at dusk signals the transition between a “wild,” self-seeded garden and a modern park that galvanized an international movement devoted to the adaptive reuse of post-industrial places, powered by new ideas rooted in the concept of greenness and sustainability. The fact that the official opening of the High Line at the Rail Yards coincided with the People’s Climate March made the experience of being here all the more powerful. One could justifiably feel, standing in the “park in the sky” at the spot where the March ended and participants began streaming in, that you were, for just that one fleeting little moment, in the most hopeful place in the world.

It makes it all the more appropriate that a visitor’s first footsteps in the High Line at the Rail Yards pass over a little knuckle in the pavement known as “The Crossroads.” Some day in the future, when the massive Hudson Yards neighborhood is complete, The Crossroads will be the only spot in the park where you could walk in any direction of the compass. But for now, visitors are irresistibly pulled west toward the Hudson River, into a newly designed section that’s remarkable for its sense of openness and natural light.

If William “Holly” Whyte were still alive he would be smiling, because in this new area the architects have conceived a whole new vocabulary for the humble act of sitting and hanging out in the city. There’s a “peel-up” bench that see-saws (and gives your calf muscles quite a workout in the process…); love seats that allow couples to engage in conversation while facing each other; a bench that doubles as a xylophone; and long tables where you can quietly work at your laptop, do some urban sketching, or enjoy a picnic with a friend.

Which gets to one of the most striking differences between the newly designed section of the Rail Yards and the rest of the park: there are lots of things to do here. Many visitors love the High Line because it was designed for promenading or just sitting quietly and watching the world go by. In the warmer months you can get a bite to eat, but essentially that’s it. It’s the Slow Park, and that’s always been part of its charm. The Rail Yards is without doubt the most beautiful part of the park, with its expansive Hudson River views and wide, sunlit plazas, and it is indeed a spectacular place for promenading and observing. But there is also much to do here, especially if you’re a kid.

The Pershing Square Beams: Just for Kids

Kids now have a place of their own on the High Line, and it’s one of the few spots in New York City where adults are not allowed unless accompanied by a child. This area was created by removing a section of the original steel beams, then covering the remaining ones with a thick layer of silicone. The result is a cool space filled with nooks and crannies for investigation and romping. A periscope offer’s a kids’ eye view of the Rail Yards, and a special tube between beams allows them to have private but amplified conversations across a distance. On opening day I overheard one little boy bellow into the tube: “I love you, mommy.”

Best of all, The Beams allows kids to get right inside the structure of the viaduct itself and see how the whole thing was put together. The engineering seems to intrigue them; one day this week a little girl interrupted her game of leaping from beam-to-beam to exclaim to her mother: “Look, those are rivets!”

Walk the Rails, Watch the Trains

Ever since the High Line opened people have been yearning to walk on the rails. It’s one of the most natural things in the world, like whistling or humming while you work, but it’s not allowed in the park because the tracks cut through garden beds that would be damaged by heavy foot traffic. In the new section, the designers created three “Rail Walks” so visitors can stroll between the tracks or hop on a rail and walk along it. As you move along, balancing on the rails, you can gaze down at real trains as they enter and depart a working rail yard: the commuter trains of the Long Island Railroad. Having dropped their passengers off at Penn Station a few blocks east, they proceed to the Rail Yards where they park until it’s time to make the return trip.

See the Past and Future at Once

But what takes your breath away in the new High Line at the Rail Yards is the “wild” section. What makes this such a powerful place is the fact that it has been left alone. I think this section, which wraps around the Western Rail Yards, is one of the most beautiful, inspiring places in all of New York City. An “interim walkway” now cuts through the plants, grasses and trees that spontaneously grew here after the trains stopped running in 1980. The temporary path was born of financial exigency – it was the quickest way open up the entire Rail Yards section, even though funds only existed to formally design part of it – but it offers an experience that is truly priceless. Here is a central part of the High Line’s narrative, an introduction to the real, wild garden that inspired the planting and design scheme throughout the entire park. Everywhere else on the High Line the tracks were taken out for remediation of the rail bed, including the removal of asbestos and lead paint, then replaced along with new plants that came from a nearby nursery. Here, the tracks remain in exactly the same place they were when the trains rumbled along them, surrounded by shrubs and perennials that have grown here, unseen, for decades. All around are breathtaking views: of the busy Hudson River to the west and vast, open stretches of Manhattan to the north, east and south.

In the middle of the wild section is a seating area made of long, wide timbers stacked on top of each other. The genius of this arrangement is that you can turn your back on the city and gaze out at the boat traffic and constantly shifting light along the Hudson River.

Or, you can turn your back on the river and watch a whole new city rising around the Hudson Yards, a neighborhood-in-progress that will, when it’s completed some twenty years hence, be twice the size of Rockefeller Center. If you’d like to watch a civilization in the constant act of reinventing itself, there’s no better place than here. All around you are the markers of time: shiny new buildings of the future, crisscrossed by construction cranes and men in hard hats; commuter trains keeping to their schedules, coming and going around the clock; rusty tracks from the old freight railroad, now overgrown with native and exotic plants; children of all ages playing and engaging with the place.

Pete Seeger’s sloop Clearwater passes between the High Line at the Rail Yards and the first section of the Palisades during the People’s Climate March

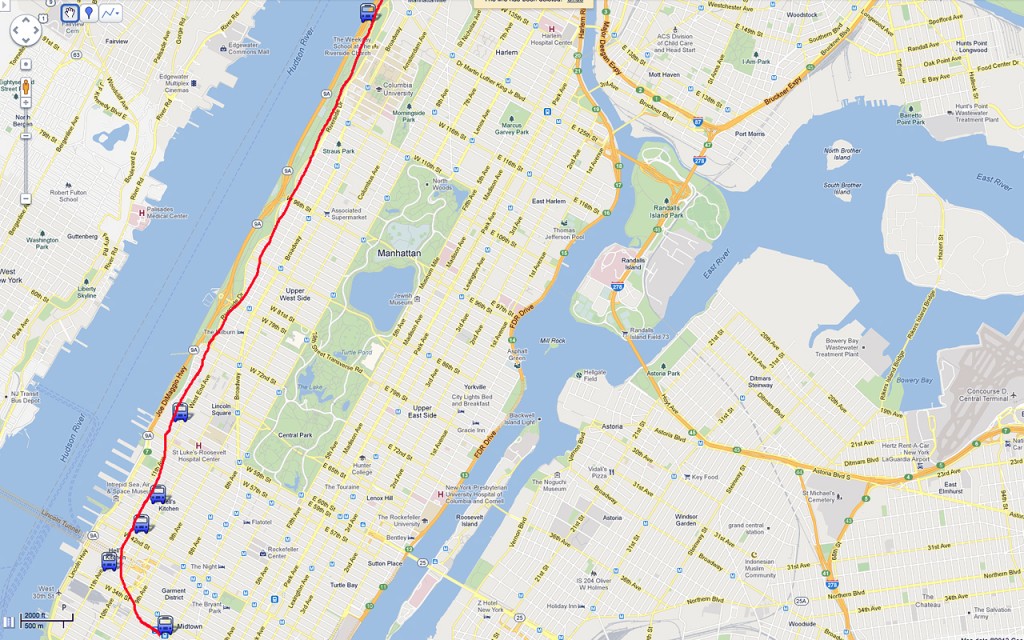

Time is in the landscape too, beginning with the Hudson River, carved in the last Ice Age some 20,000 years ago and used by us for the past four hundred or so as a primary force of American life, culture, commerce and art. Never content to let the river be, we’ve exerted our force on it in countless ways, and a good place to consider that is on the High Line’s new “Catwalk,” a raised path that crosses 11th Avenue. According to the Welikia Project, which collected massive troves of data on the ecology and topography of Manhattan Island before the Europeans arrived, in 1609 the Hudson River flowed just below today’s Western Rail Yards. (Marty Schnure of Maps for Good used the Welikia-Mannahatta data to create a special map for On the High Line that shows the original 1609 shoreline in relation to the entire park. Click the image of the map below to enlarge it and see the detail.)

Centuries of landfill later, we have the the High Line, Chelsea Piers, the Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum, the West Side Highway, and dozens of old warehouses that are home to art galleries, tech, design and media firms — including the architects of the High Line itself, Diller Scofidio + Renfro, who work in a large studio space in the Starrett-Lehigh Building.

But a look across the river takes us much, much further back in time. On the western bank of the Hudson, just across from the Rail Yards, you can see the first segment of the Palisades, created at the end of the Triassic Period some 200 million years ago. It’s a place where ancient geology meets classic human folly: in July 1804, Alexander Hamilton, former Secretary of the Treasury, was shot and killed here by Aaron Burr, then the Vice President of the United States. In fact, this craggy spot in the town of Weehawken was a popular dueling ground; DeWitt Clinton fought a duel here in 1802 and Oliver Hazard Perry fought one in 1818. Today, a railroad runs through it.

The new section of the High Line offers these and countless other points of contemplation. It’s a gift of extraordinary, timeless value. Every time you visit you will see something new against something old; it’s the ancient dance we do in New York, and there is no more beautiful, inspiring, place to bear witness to it.

The High Line at the Rail Yards, opened September 20, 2014

Plant design: Piet Oudolf

Landscape Architects: James Corner Field Operations

Architects: Diller Scofidio + Renfro

Lighting: L’Observatoire International

More information at TheHighLine.org