The thing that most surprised me on my first visit to “Little Island,” Manhattan’s newest flashy park, was how much I wished I were somewhere else.

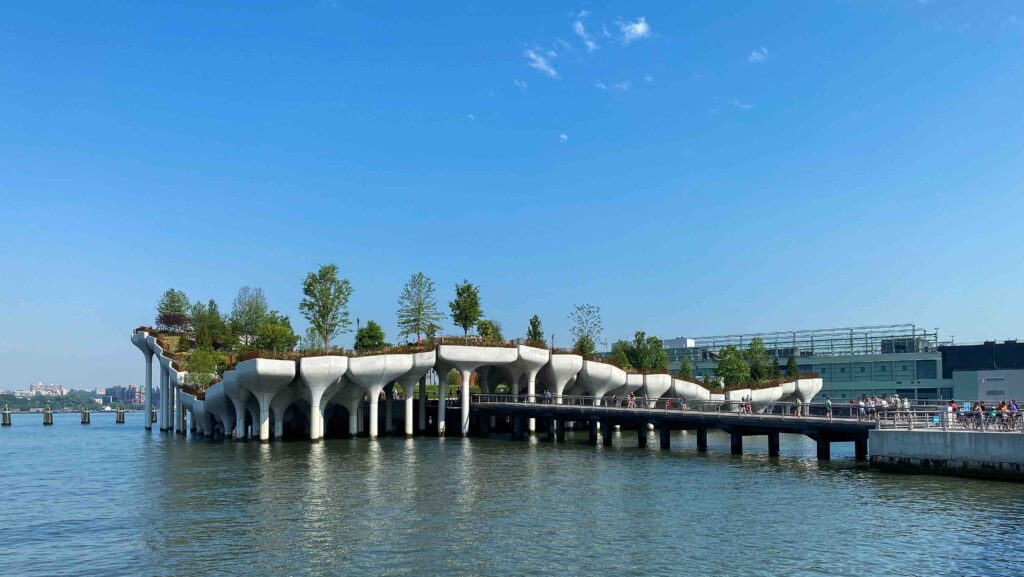

It’s not that I wasn’t brimming with anticipation about the opening of this place. I had been watching and photographing the development of this riverine park for years; studied designs that were published online; followed the legal controversy as it unfolded, like a metropolitan opera, in the pages of newspapers and websites. Little Island is a strikingly unusual outdoor space, one that rises improbably “atop a bouquet of tulip-shaped columns,” as Michael Kimmelman so perfectly described it in the Times. Its undulating pathways open up views no New Yorker has ever seen before, and along the way they treat us to a quite stunning mix of materials, colors, and shapes. It’s the experience of juxtaposed elements — hard & soft, high & low, bright & monochrome, historical & contemporary, intimate & expansive, industrial & high-tech — that you expect to encounter in a great art museum.

But as I walked, climbed and gazed around me, both at the people and the landscape, the same thought that has been dogging me since I first heard about Barry Diller’s fantasy island came back to haunt me. Stunning, original, improbable, innovative as it is — and Diller Island is all those things — how extraordinary it would be — how breathtaking and awesome and inspiring — if it were in the South Bronx, or some other part of New York City that’s underserved by world-class parks. And how stunning it would have been if such a park had opened in this of all years, after the ravages of a pandemic and the Black Lives Matter movement made it impossible to un-see the many inequities that are stitched through the landscape of our city.

We’ve known for centuries how important beautiful outdoor spaces are to human health and happiness. In an 1850 magazine article Andrew Jackson Downing asked: “Is New York really not rich enough, or is there absolutely not enough land in America, to give our citizens public parks of more than ten acres?” A contemporary, James Gordon Bennett, declared in the New York Herald that a public park is a pair of lungs. And Tony Hiss, in his book The Experience of Place observes that Frederick Law Olmstead, co-creator of Central Park, “seems to have remarkably anticipated Christopher Alexander’s recent finding that people will not make regular use of a city park if it is more than about 750 feet, or three minutes’ walk, from their doors.” We have known forever that parks are essential. We have known forever that proximity to parks is essential. And yet….

Here on the Far West Side of Manhattan, in the neighborhoods of Hell’s Kitchen, West Chelsea and the Village, we have an embarrassment of riches: world-class parks that stretch for miles and miles. The High Line, Hudson River Park, Pier 84 with its kayak rentals, Pier 64 with its historic ships, Chelsea Waterside with its special amenities for kids, Pier 62 with its giant tent that’s invariably swelled by the music of saxophone or harmonica.

We didn’t need another new, world-class park here. What we need is new, world-class parks in places where they don’t exist. This is what has been bugging me since Mr. Diller’s project was first announced in 2014, by which point the High Line had become so crowded with tourists it became necessary, for me at least, to visit at the break or dawn or during thunderstorms. Parks in New York City are for New Yorkers. It’s wonderful that tourists love them too, but tourists are traveling people, and they will go where the great places are.

So while Diller Island — I feel compelled to call it by its original name, after the very rich man who built this park outside his office window — is a stunning, original, innovative, improbable, place that brings together horticulture, entertainment, glorious views of the Hudson River, industrial history (the pier that once sat here, Pier 54, was used by the Carpathia to discharge survivors of the Titanic, whose original destination was Pier 59), to me it is a lost opportunity. And as a lifelong New Yorker, it just breaks my heart that we couldn’t give this gift of place to our neighbors who really need it.

Click here to read more about the fascinating backstory of Pier 54. Click here to order Christopher Alexander’s groundbreaking book A Pattern Language. The reference I cited above, quoted by Tony Hiss, is on pp. 308-309.

Amen.

Absolutely agree with this very well written piece.

Maybe Diller and Furstenberg will read your piece and be inspired to build another in the Bronx or Queens.

Well said!

I can’t wait to get there, sometime, with your wise words echoing in my ears. Yes. No need for it to be where it is.