Yesterday I posted two ideas for shooting the Lehigh Valley No. 79 as it sails north on the Hudson River later this week to a Coast Guard-mandated drydock inspection in Waterford, NY. [Follow @museumbarge on Twitter for schedule details.]

Here’s another suggestion for those who like the aerial perspective: the 8th floor terrace of the new Whitney Museum. If you point your camera west you’ll get a shot of this historic barge, a rare monument to the Lighterage Era and currently a floating museum based Red Hook, as it passes the grand old Hoboken Terminal.

Designed by architect Kenneth Murchison, the Beaux Arts Terminal greeted passengers in a grand style by allowing the sun to stream through stained-glass windows made by Louis Tiffany. It opened as a rail and ferry terminal in 1907, just seven years before the Lehigh Valley No. 79 was built in Perth Amboy. At night, the big red letters on the eastern facade of the Hoboken Terminal light up to read ERIE LACKAWANNA, and the recently restored clock tower marks time for vessels passing by.

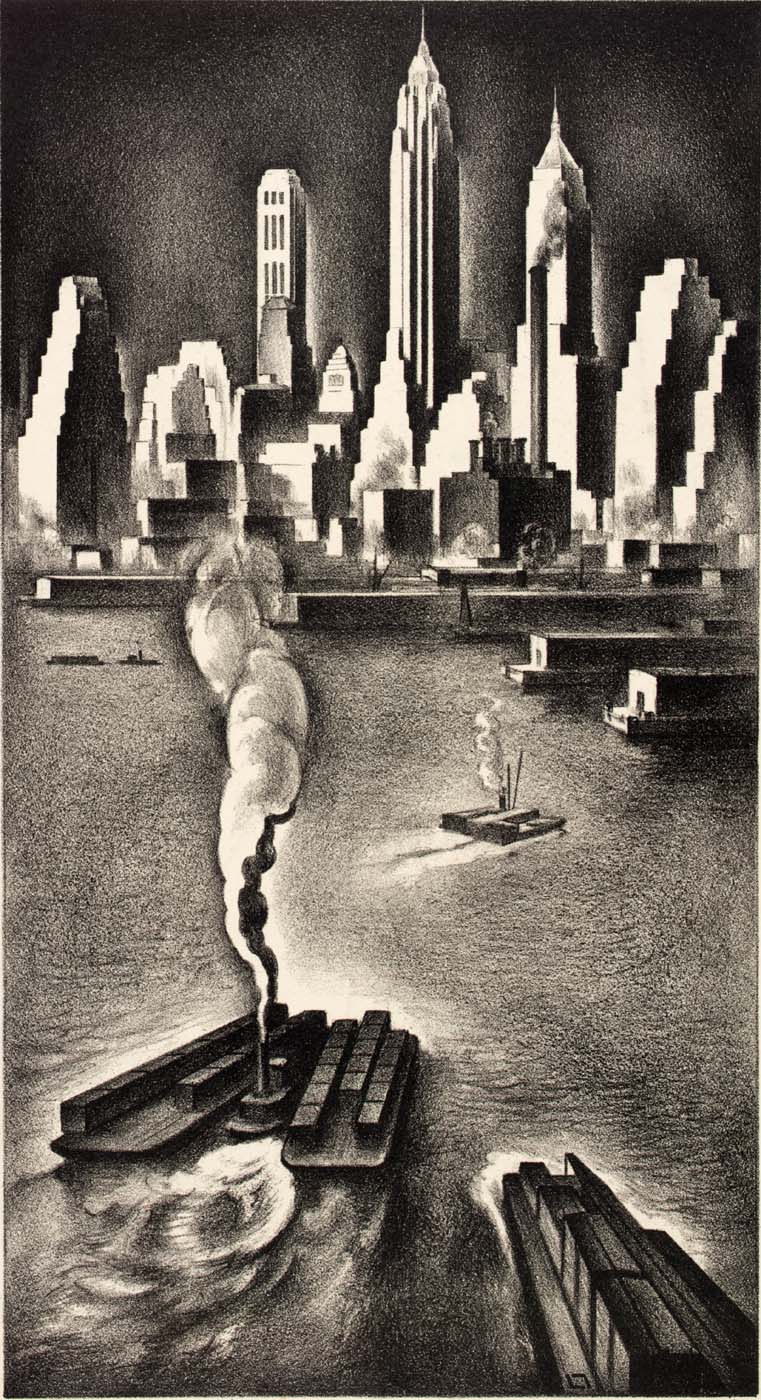

There are a million other reasons to visit the Whitney (see my piece here about the history of the site the new building occupies), but on my mind today is Louis Lozowick, an Art Deco-era painter who emigrated from Russia the year before the Hoboken Terminal opened. I first discovered his work in the WPA Guide to New York City, published in 1939 with the intent to “indicate the human character of the city, to point out the evidence of achievements and shortcomings, urban glamor as well as urban sordidness.” The editors selected Lozowick’s wonderful drawing of a railroad barge being pulled by a tugboat to illustrate Lower Manhattan in the 1930s.

After seeing that evocation of the lighterage system I embarked on a hunt for more of Lozowick’s work, found a giant archive on the Smithsonian’s website, and got lost for hours. He was devoted to bridges, buildings, river traffic — particularly tugboats — and the industrial iconography of cities: gantries, factories, smokestacks, water tanks: many of the elements folks love about the historic landscape of the High Line. Most of Lozowick’s work was in black & white, which contributes a kind of moodiness and authenticity to his scenes.

It’s easy to fall in love with Louis Lozowick, and as I clicked through the pages of the archive I was amazed at the range of subjects he painted. His wife told the New York Times that “He always did what he wanted to do, he didn’t care about prevalent styles, nor about the market. He was doing abstractions when others were doing realist work, and when others were doing abstract things, he was doing realist pieces.”

What took my breath away at the Whitney Museum was Lozowick’s drawing of a lynching, which is part of a powerful collection of prints made to support a 1930s anti-lynching bill in Congress. It’s completely unlike the rest of his work, in part because it evokes a force of such raw humanity. There are a few other Lozowick’s in the Whitney’s inaugural show, “America is Hard to See,” including some of his abstractions; you can see all of the museum’s holdings here, including “Lynching” (1936).

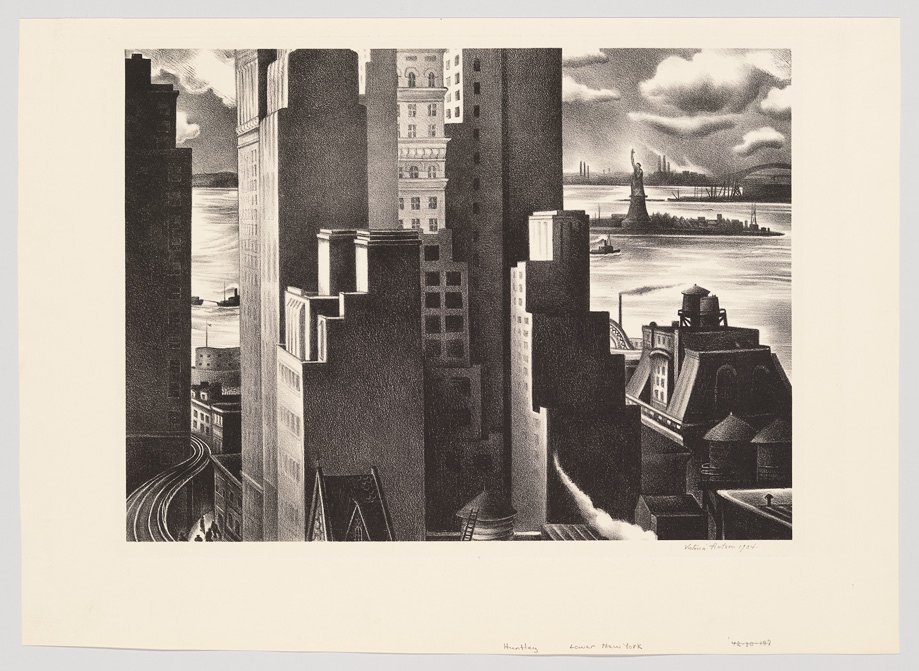

And: if you’re there to watch the Lehigh Valley No. 79 sail by later this week, be sure to check out Victoria Hutson Huntley’s 1934 depiction of “Lower New York,” which includes an elevated railroad and a couple of tugboats; it’ll put you in just the right mood. The Whitney kindly allowed me to reproduce Huntley’s lithograph here. [As always, click an image to enlarge it.]

Victoria Hutson Huntley, “Lower New York, 1934.” Lithograph. Whitney Museum of American Art, currently on view in the inaugural exhibition “America is Hard to See” (May 1 – Sept. 27, 2015). Used with permission.

Okay, I confess this post digressed from its original purpose: to identify the best aerial spot in Manhattan to photograph the Lehigh Valley No. 79 as it begins its northerly voyage in a few days. But this is what happens when you start thinking about railroads, tugboats, the Hudson River and Manhattan’s edge. Everything around us is connected to the past, and the Whitney is both glorious museum and grand, public parapet that puts so much of our cultural and industrial history on display. It’s what the WPA writers considered “urban glamor.”