Hurricane Sandy’s high water mark. West 22nd Street, near 11th Ave.

When I was researching my High Line book I came across an autobiography published in 1864 by a professor at General Theological Seminary, Rev. Samuel H. Turner. In his book Dr. Turner recalls the days when there was a hill and an apple orchard behind the Seminary, and 21st Street was known as Love Lane. There was also, running north along the western edge of General Theological Seminary, something that would surprise a modern visitor. The Hudson River.

The city was just a bit smaller in those pre-landfill days, and Dr. Turner describes how, at high tide, the river “washed what is now the Tenth Avenue.” The Hudson presented many challenges to the Seminary community, including depositing at its front door waves of mud that was ankle deep. One winter, so much mud piled up around the building that “it was almost inaccessible, except on horseback or in a carriage.”

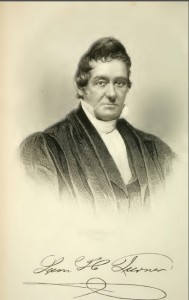

Rev. Samuel H. Turner

These days, as I walk down 22nd Street toward the West Side Highway, I find myself thinking about Dr. Turner and his mud problems. You have to look carefully, but there, running along several buildings on the north side of the street, is Hurricane Sandy’s high water mark. Flecked with mud and grime, the crusty water line is an inch or so thick and stands about 5′ above the sidewalk.

No one has yet come to wipe this reminder away, though it crosses several properties. Here, on a spot where 200 years ago Samuel Turner and his colleagues would have seen whitecaps and sailing masts, is a strip of dirt from the deep caverns of our ancient riverbed. Sandy’s water line stands as an enduring, muddy cicatrice that marks the spot where briny waves of the Hudson River stormed past a restaurant, a furniture maker’s shop, a few art galleries, a city-run shelter for men, and some homes on the evening of October 29th.

After the Civil War the city began selling “water lots,” and developers rushed in to buy up chunks of the Hudson River, which they filled in and developed into factories, warehouses, and living quarters for the surging immigrant population that was flooding New York. The building where I live, which hugs the High Line east of Sandy’s water line on 22nd Street, was built in 1888 as a cigarette packing factory. Later it became a furniture factory for a company called Spears, which cut giant window bays into the brick walls and attached a loading dock that connected to the High Line, thus facilitating the shipment of furniture along the New York Central Railroad’s elevated freight line.

The High Line roughly follows the landfill line on the far west side of Manhattan. I’m pretty sure this is why the cabinets in my office started rattling and tilting during the freak earthquake of August 2011, while friends who were working on good old Manhattan schist in midtown felt nothing. Back in the early 19th century there was a river running beneath us. Eager developers mastered some part of that river and built upon it what was first a center of industry and later became a magnet for artists, geeks, hedge fund guys and tourists. But what we now know, courtesy of Hurricane Sandy, is that this river will rise up from time to time and leave its watery mark on our real estate and on our lives.

No horse, no carriage, no automobile will ever be a match for the force that came through here two months ago.