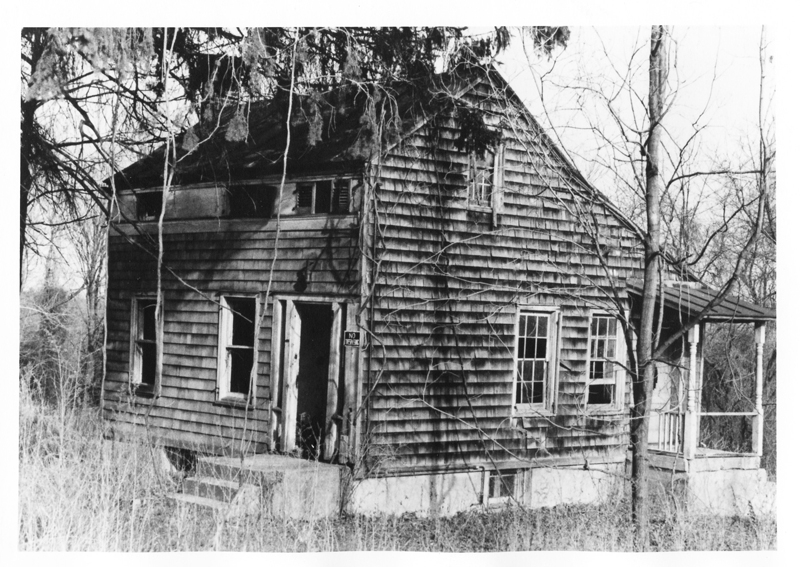

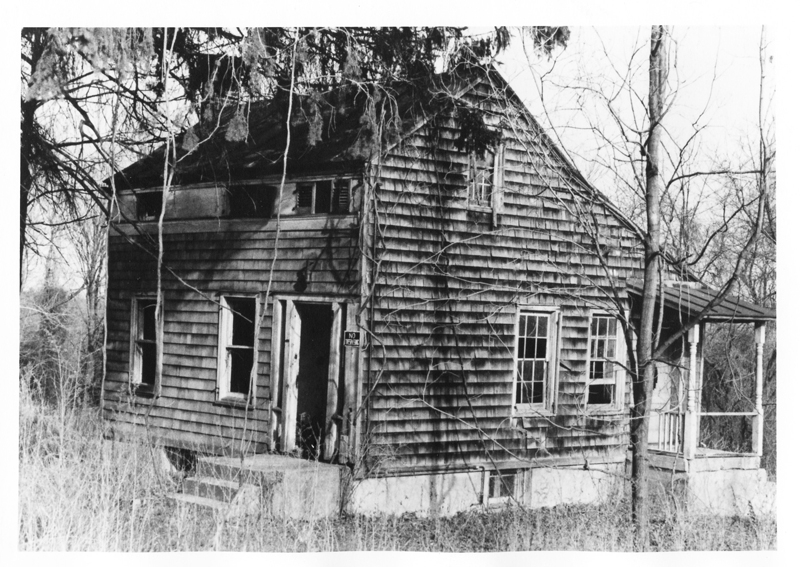

Germantown School House, early 1980s

Seventeen years ago we were spending weekends in a small 19th century converted saltbox in Germantown, New York, that had once been home to the local school teacher. It was also her classroom. I bought the house in 1985 from an Episcopalian minister who was partly deaf but swore he could still hear the voices of 1860s school children echoing across the ancient floorboards. He loved the old wreck so much he hired a local contractor to restore it. The item he prized most highly about the lovely little house was a stairway bannister that dated from the Civil War. It was a wonderful place where I spent many happy years, but little did I know that something — or, to be more precise, hundreds of thousands of something — was lurking below ground.

Cicadas.

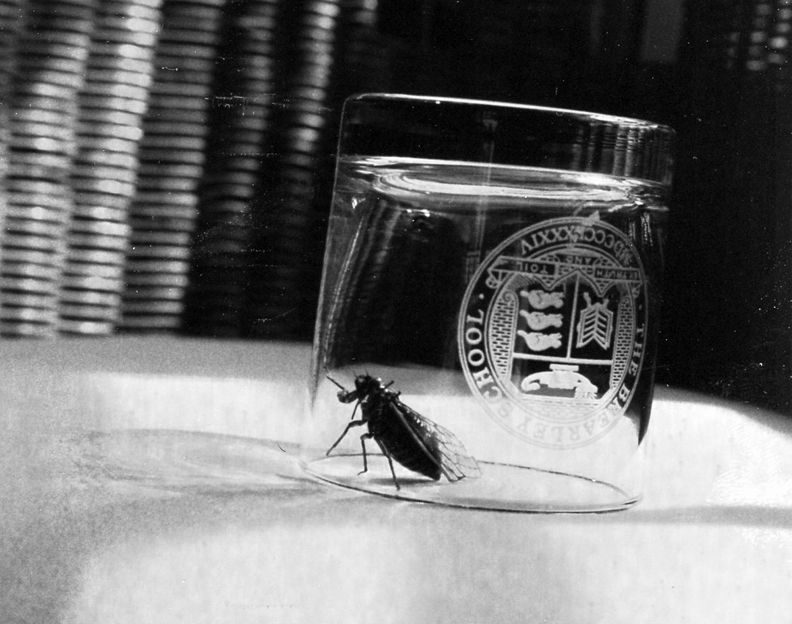

We’re hearing a lot about the seventeen-year cicadas these days. They are coming soon, and the memories of 1996 are returning to me like scenes from a Stephen King novel. For weeks we couldn’t go outdoors without being dived-bombed by hundreds of them. Our dog tried to catch them in his mouth as they flew by, but they pelted him with their orange wings and drowned out his barking with their endless buzz. We would race to the car in the driveway, swatting locusts from our heads with both hands, and then slam the doors closed. Crunch. Many cicadas died a quick, Toyota death, but inevitably one would make it inside, onto someone’s lap.

“Well,” I once said to Ann, “it’s better than mouse, don’t you think?”

Disgusted silence.

The cicadas made so much noise we couldn’t read, or carry on a sensible conversation with the windows open. When I played the piano I was accompanied by an orchestra that droned on and on in a weird, endless, Arnold Schoenberg track. It was like living in a chapter of the Bible. For six weeks the cicadas hurled themselves at the windows and doors, flying their crazy missions, 24/7, from pillar to post. And then, finally, they all died, and it got very, very, quiet.

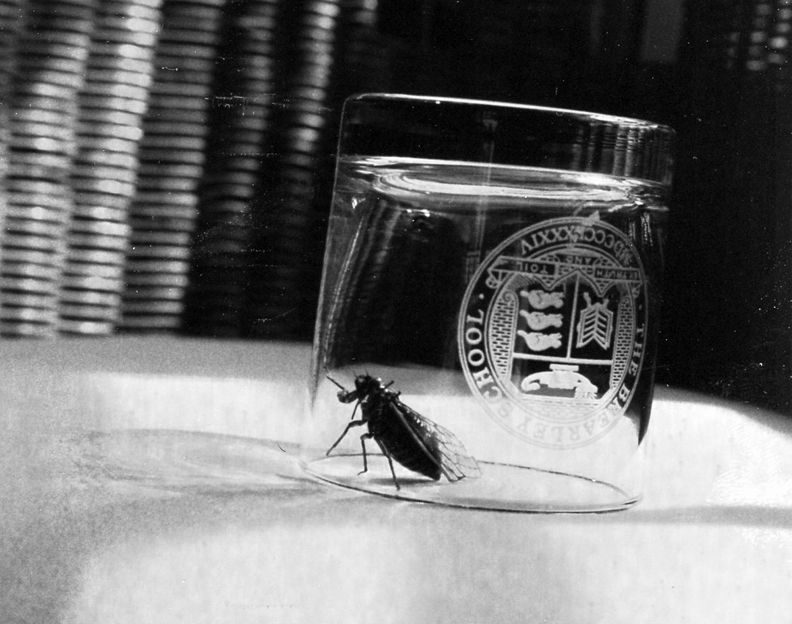

17-year cicada, trapped by the author in a highball glass, 1996

I don’t know why it is that one patch of land would be more cicada-rich than another. Perhaps it’s that the Germantown place was once farmland, and the soil was rich and pliable, perfect for a cicada to hunker down and spend seventeen quiet years. Inexplicably, friends nearby didn’t have nearly as many of the creatures as we did. We were, it seemed, Cicada Ground Zero. Today we spend weekends five miles north of Cicadaville but on a rocky mountain that seems — or perhaps I am just in Pollyanna mode — highly cicada-unfriendly. We shall see.

Meantime, I’m taking to heart the advice of David Haskell, I writer a greatly admire. In a blog post yesterday he urges those of us who are “lucky enough” — his words — “to live where the action is, to remember what you’re hearing: seventeen years of stored sunlight being released all at once as acoustic energy. The terrestrial end product of nuclear fusion exploding into your consciousness.”

While I’m waiting for the cicadas to rejoin us, does anyone have a good recipe?