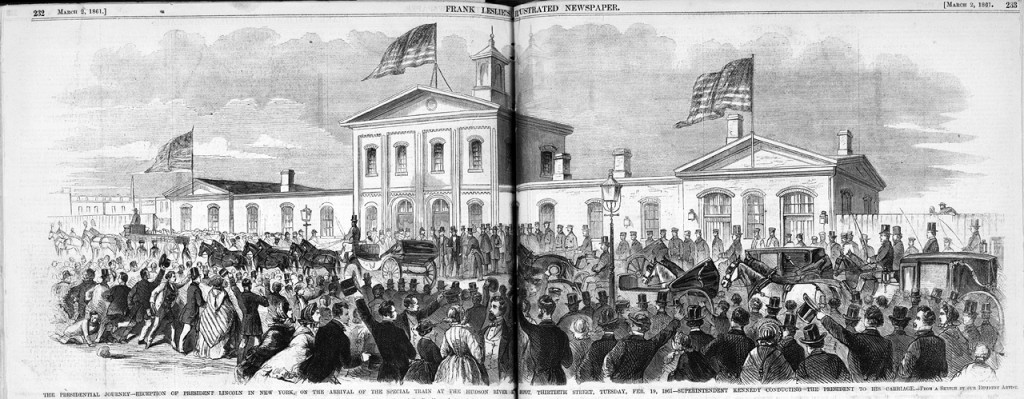

I’ve written about Abraham Lincoln many times on this blog, always identifying as sacred ground the spot where the Morgan General Mail Facility now stands. This is because Lincoln passed through the area twice in the 1860s when it was the site of a train station, owned and operated by the Hudson River Railroad. The first time was on February 19, 1861, when the President-elect was en route to Washington, DC for his inauguration. Three years later, Lincoln’s funeral train passed through the depot on its long journey west to Springfield, Ill. After many years of searching for a photograph of that depot, I finally found one at the New-York Historical Society, and published it here.

The first occasion was memorialized in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. The illustration shows the depot with three large American flags in the background; in front of the station Lincoln is being escorted to his carriage by superintendent Kennedy of the Metropolitan Police. [click the image to enlarge it and see Lincoln in his signature top hat and beard.]

Abraham Lincoln’s Special Inaugural Train at the Hudson River Railroad Depot, 1861. From Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, courtesy the Library of Congress

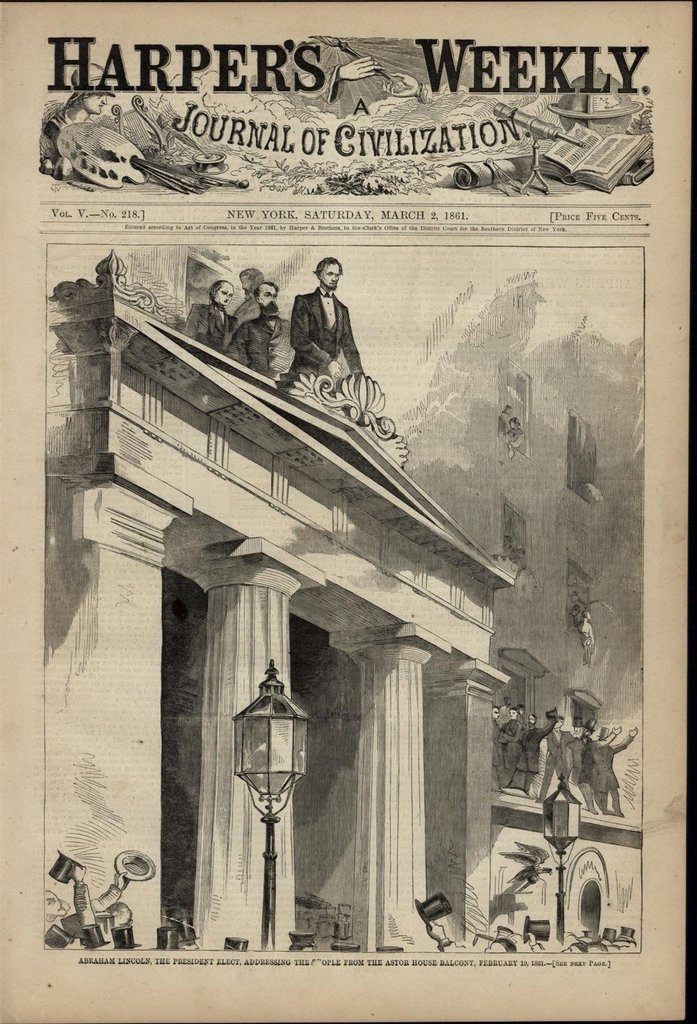

Last week at the terrific Walt Whitman show that’s currently on view at the Morgan Library I learned some intriguing new details about Lincoln’s visit to New York. Earlier that same day, February 19, 1861, Lincoln addressed a large crowd from the Greek revival portico of the Astor House, at the time considered New York’s finest hotel. Harper’s Weekly, the “Journal of Civilization,” put the story on its front cover in the issue dated March 2, 1861:

The Morgan’s exhibit explains that Lincoln’s appearance came at “a time of immense danger to the country and to him personally.” Later, according to the curator, it was revealed that a spy named Kate Warne had traveled to New York to warn Lincoln of an assassination plot. She may even be visible in one of the windows in the background of the Harper’s drawing. Warne, who was the first female detective in America, worked for the Pinkerton Agency and had gone undercover in Baltimore to investigate the threat. She disguised herself as “a flirting Southern Belle,” gained confirmation of the plot, and reported it to authorities in New York. Also present that day but not in the Harper’s Weekly illustration: Walt Whitman, who in true New York style was stuck in traffic on an omnibus nearby.

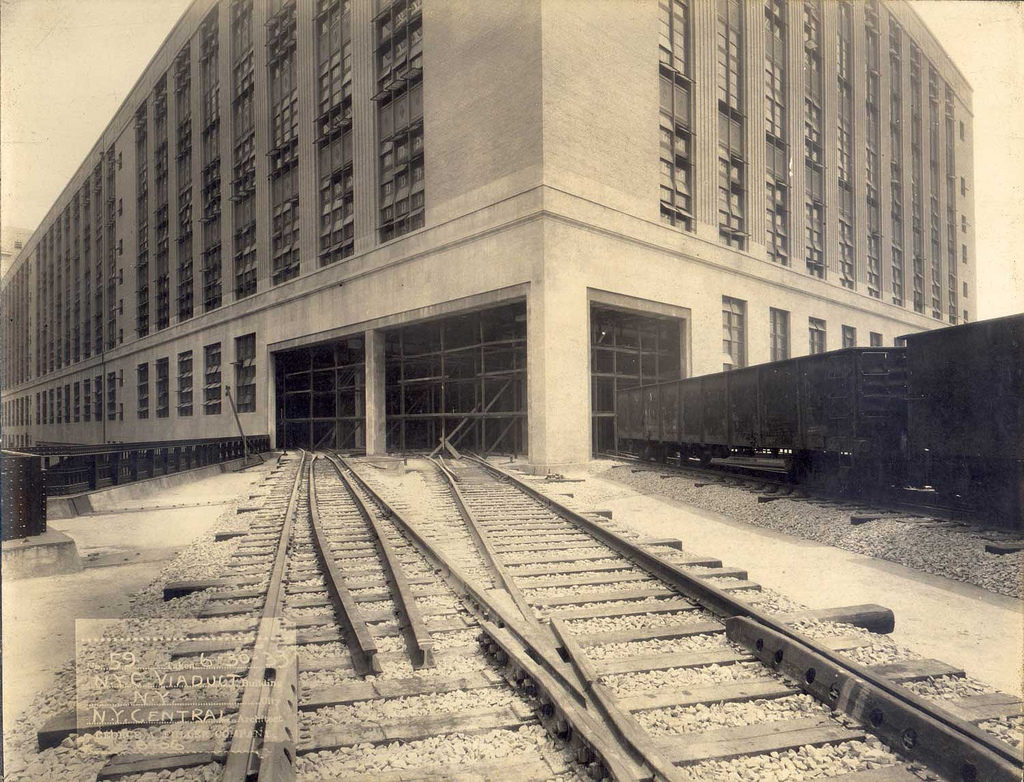

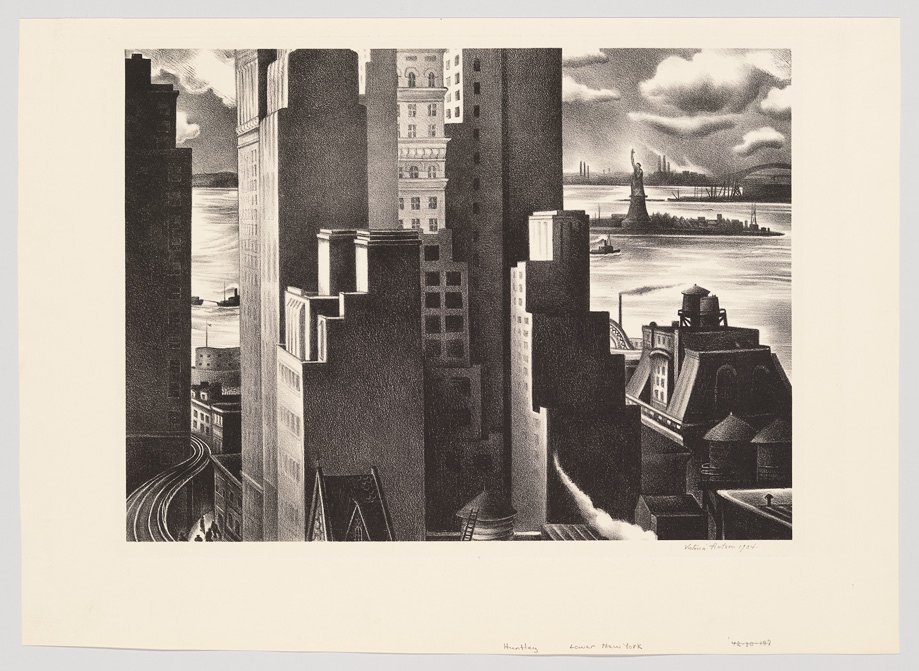

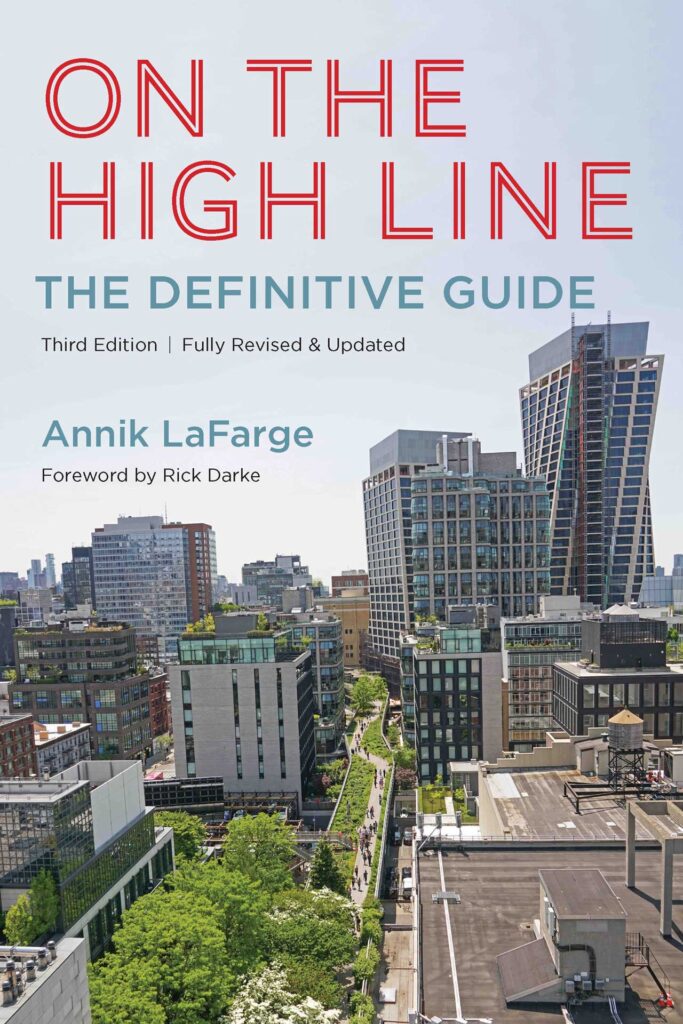

Later that day Lincoln continued his journey, in the presence of a strong police force and via the Hudson River Railroad’s brand new station. He was the very first passenger to use what was clearly an enormous and grand structure. The illustration in Frank Leslie’s newspaper is the only image I’ve been able to locate of this long-lost beauty. Many years later it was torn down and replaced with a massive sorting facility. In the freight rail era of the High Line, which began in 1934, boxcars filled with letters and packages from across the United States made the final leg of their journey over the spur that crosses Tenth Avenue, passing through the (now bricked-up) openings in the northwest corner. The photo below was taken just before construction was completed:

Standing sentry on the just-opened Tenth Avenue Spur of the park that succeeded the railroad is “Brick House,” a 16′ high bronze sculpture by Simone Leigh that, according to Friends of the High Line, “encompasses several architectural and cultural references in tribute to the strength of Black female beauty.” The architects, as per tradition on the modern High Line, have left the original train tracks in place, so today they bracket this imposing, and inspiring, work of art.

Sacred ground indeed.

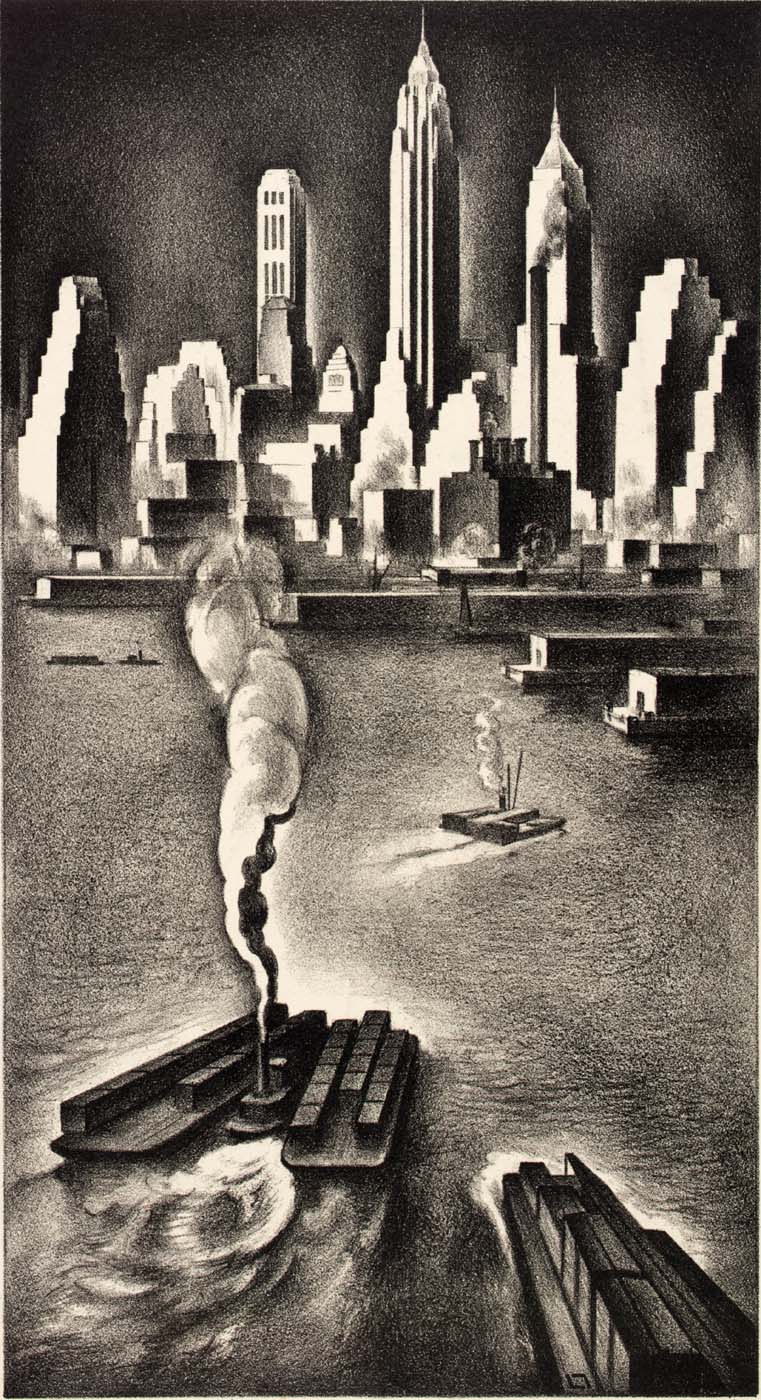

Here’s an earlier, aerial shot that shows the wider landscape:

The Morgan General Mail Facility, on ground once occupied by the Hudson River Railroad © Annik LaFarge

SOURCES:

Christopher Gray, “Where Lincoln Tossed and Turned,” The New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/27/realestate/27scapesready.html

The Morgan Library, “Walt Whitman: Bard of Democracy,” June 7 – September 15, 2019 https://www.themorgan.org/exhibitions/walt-whitman

Wikipedia, Kate Warne, and Barbara Maikell-Thomas, “Kate Warne: First Female Private-Eye,” by Barbara Maikell-Thomas, http://www.pimall.com/nais/pivintage/katewarne.html