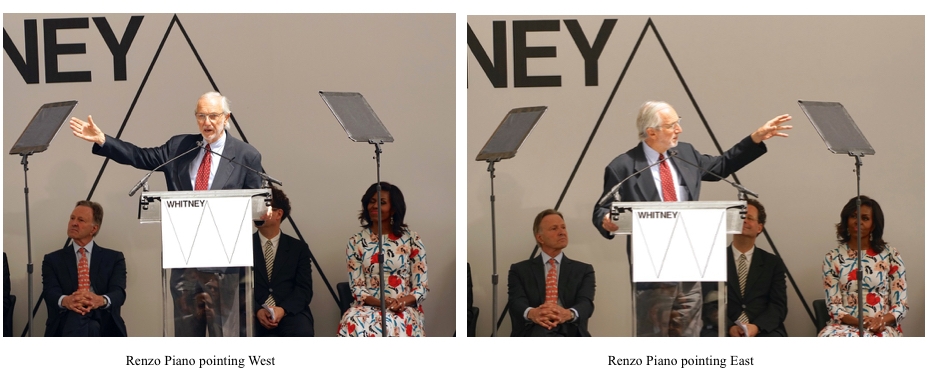

When architect Renzo Piano speaks about the Whitney Museum of American Art he uses his entire body to illustrate the artistic intent of his new building. During the museum’s official dedication ceremony he gestured first to the east, and a view that cuts across Manhattan Island. “This building talks to the city,” he said, then turned left and pointed to the Hudson River. “It also talks to rest of the country: all the way west, to Los Angeles, if you look carefully,” and then to the world beyond. This new building, with its massive windows and expansive 360 degree views, seems designed to enable a sort of outward-looking contemplation and engagement that most museums, with their emphasis on what’s inside, right in front of you, don’t encourage. “I’m pretty sure that beauty will save the world,” Piano said, and this new home for one of the country’s foremost collections of American art makes the point at every turn that all the beauty inside is made more powerful by its connection to a greater, wider landscape.

This is the fifth article in my series “High Line Architecture.” Like the previous other pieces, it’s not an architectural or aesthetic review but instead a look the history of the place a building occupies, and a contemplation of how the landscape around the High Line has changed over time. (See below for links to the previous articles; as always, click an image to enlarge it.)

There’s something felicitous about the fact that this quintessentially American institution, one that celebrates creative inventiveness and innovation, sits on land that’s man-made. When the first Europeans arrived at these shores in 1609, they would have sailed or paddled over the spot where the Whitney now stands. Gradually, beginning in the early 19th century, this watery area was filled in so an early generation of developers and real-estate schemers could start building stuff on it. Like much of the far West Side — virtually everything west of Tenth Avenue, including the High Line — the Whitney sits not on Manhattan schist but on landfill. (Interestingly, as the map below shows, the High Line roughly follows the landfill line all the way to the Rail Yards. This makes a walk from one end of the park to the other a great way to contemplate not only how we transformed what was on our island but also how we transformed the geography of the island itself.)

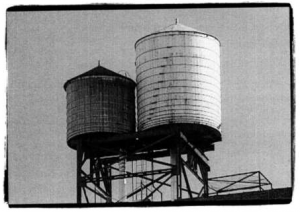

The huge complex of buildings across the street from the Whitney, the West Coast Apartments, is another example of ingenuity: modern commercial refrigeration was pioneered here. In the late 1890s, the Manhattan Refrigerating Company developed one of the earliest and most technologically advanced cold-storage facilities, based on a complex system of underground pipes that fed cooled water from the Hudson River into a huge, multi-storey warehouse that eventually would connect with the High Line, itself an innovation that opened in 1934.

This little patch of land(fill) also has a long and distinguished foodie history. As early as 1879 there were outdoor farmers’ markets here; the neighborhood was filled with merchants who came from all over New York state, from Long Island to the Hudson Valley, to sell poultry, meat, seafood, eggs, butter, vegetables, beer. You can still trip over the Belgian block (also known as cobblestones) that were here long ago, or take refuge from a downpour under the metal canopies that sheltered grocers in rainy weather.

The photo below is from the first decade of the 20th century and shows the area where the Whitney now stands. This year two restaurants — Santina (under the High Line) and Untitled (in the Whitney) — opened on this very spot, each in a virtual glass box with windows onto the street and a commitment to serving food made from local farmers and growers. Generations removed from the men who came here with horse and donkey carts, they include a welcome 21st century cohort: urban farmers who grow produce on rooftops in Brooklyn and Queens.

But the rich food history stretches back even further: long before there was a railroad or a farmers’ market here, the area was a prime hunting and fishing grounds for the Lenape people. Using data from the Welikia Project, the 1609 shoreline map also shows the location of a Lenape Indian trail that runs over land now occupied by the handful of remaining meatpacking plants that still operate underneath the High Line and gave the neighborhood its name.

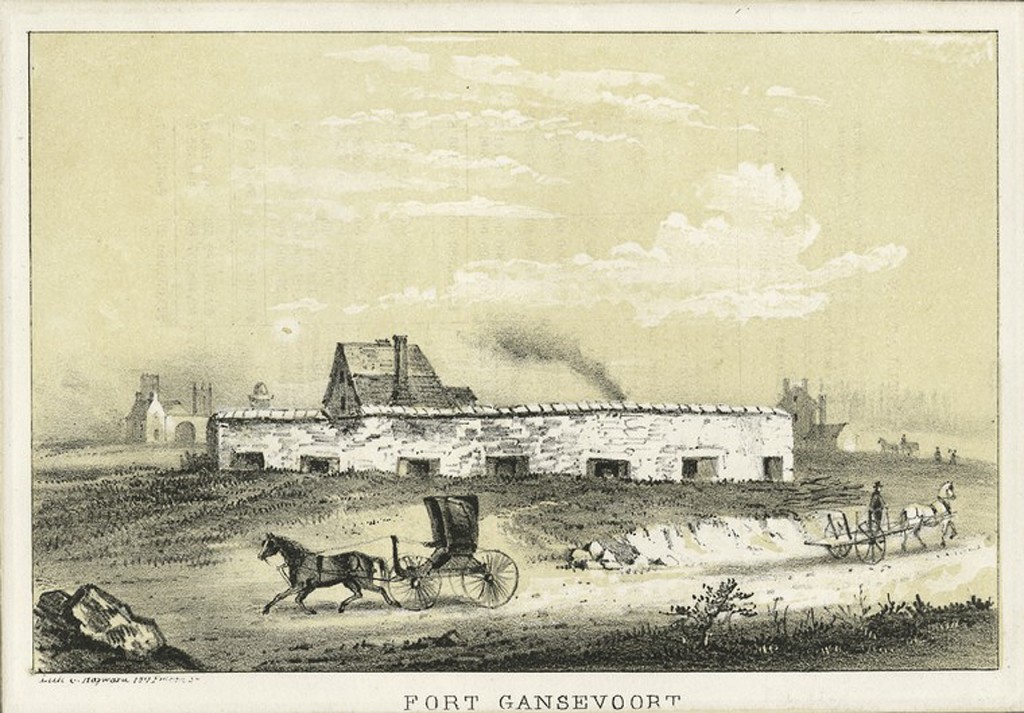

The Whitney site was also important in the military history of the United States: in 1808, in anticipation of a war against Britain, a fort was hastily built here on pilings erected in the Hudson River. Known as Fort Gansevoort, it was named after the revolutionary war hero Peter Gansevoort. Some five decades later, Gansevoort’s grandson, Herman Melville, would spend almost twenty years just across the street at the Gansevoort Dock, where he worked as a Customs Inspector.

All this history: food, trains, technology, soldiering. A bit of river at the edge of a forest becomes a fort, a farmers market, a multi-storey refrigerated warehouse with a railroad passing through it, a world-class park and now an art museum that urges us to look outward, through its many windows, onto the wide and complex world we inhabit. Inside, the museum deploys art and artists to push the boundaries ever farther and inspire and challenge those acts of contemplation and engagement.

The whole project feels experimental, even radical. On the fifth floor, the architects provided a sitting area that runs the length of the museum and faces west, encouraging visitors to sit and contemplate the Hudson River. All day long the boats go by: water taxis, ferries, oil tankers, cargo ships, police vessels, luxury yachts, cruise ships, kayaks and barges carrying gasoline and home heating oil, like the one in my photo below. On the West Side Highway cars, trucks and motorcycles rumble along. Between the river and the highway cyclists, bladers and skateboarders glide by on the bike path. All the while, visitors in the new Whitney Museum are sitting and watching. Behind and above them, racing across the wall and visible to all those mariners, drivers, cyclists and pedestrians outside, are the “Running People” of Jonathan Borofsky, an artist known for works that capture figures in movement: people walking, running, flying. This museum, resting on its man-made foundation in a place saturated with invention and history, has taken us into a new era of art appreciation, one where we are always engaging and never quite sitting still.

Piano conveyed everything the new Whitney stands for when he said, in his closing remarks: “Thank you for coming. The building is yours.”

“Running People at 2,616,216” (1978 – 79) by Jonathan Borofsky. The Whitney Museum of American Art, 5th floor, the inaugural exhibition “America is Hard to See.”

To learn more about the Gansevoort Market area of the West Village, read Tony Robins’ excellent walking tour which is filled with history and illustrations. Download a PDF or read it online here.

Architecture on the High Line: click the image below to read previous posts in the series