This third piece on High Line architecture focuses on the Morgan General Mail Facility on Tenth Avenue between 28th and 30th Streets. Of the buildings I’ve covered so far in this series (the Westyard Distribution Center next door and the former R.C. Williams warehouse a few blocks south) the Morgan has the oldest and richest back-story. Spanning three centuries, from the 1860s to the second decade of the 21st century, this massive structure and the land it sits on offer up many threads in the history and culture of New York City.

The photo above, taken from the roof of the Ohm apartment building on Eleventh Avenue, reveals much of modern story. Completed in 1933, the Morgan was built with funds and labor from the New Deal’s WPA program. It was designed to connect with the High Line and create a seamless path for the more than 8,000 mail trains that crossed the country each year on an intricate network of rail lines before ultimately proceeding south alongside the Hudson River on tracks of the New York Central Railroad into Manhattan. The last 30 feet or so of their journey took them across Tenth Avenue on a specially constructed spur that led directly into the postal facility. My photo was taken hours after the first snowfall of 2012, and you can easily see the rails on the abandoned spur and the bricked-up siding where the trains once entered the building. The photo below is from the West Side Improvement Brochure and shows the Morgan in the year it was built. Look closely and you can see a locomotive motoring through the siding (as always, click a photo to enlarge it).

In the 1990s an annex was built with a pedestrian bridge across 29th Street that connects the two buildings. The giant windows that face onto Tenth Avenue caused plenty of problems for birds, who use the Hudson River as their own transportation superhighway during migration season. For several years the Morgan topped the Audubon Society’s collision list because so many birds crashed into them and fell to their deaths in the street below, but the problem was soon corrected.

A month or so after the High Line park opened in 2009 the Times sent a reporter deep inside the Morgan, which is one of the largest mail-processing facilities in the nation, handling as many as twelve million pieces of mail in a single day. Alan Feuer, the Times’ reporter, described it as “the central nervous system of mail delivery” and remarked that the Morgan “is to the delivery of mail in New York City what Willie Wonka’s chocolate factory was to making candy.” Feuer was so impressed with the network of conveyor belts in the sorting facility that he imagined “If Dr. Seuss were to ingest peyote, then drift off dreaming of the United States mail, the resulting vision could be no less mechanically psychedelic than this.” The employees at the Morgan — there are 4,000 of them — call the 5-mile system of conveyor belts Barney after the cartoon character because it’s huge and lavender. It’s fair to say that modern mail sorting reached its peak at the Morgan.

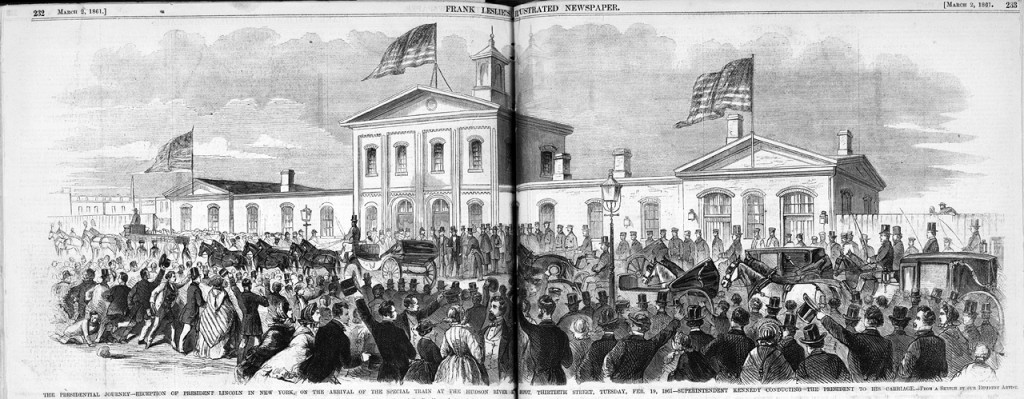

But this busy patch of land on Manhattan’s far West Side has seen much more than billions of packages, pieces of mail, and technological innovation. In the early 1860s a train station sat here, owned and operated by the Hudson River Railroad. The very first passenger to use the station was Abraham Lincoln, who passed through the brand new depot on February 19, 1861, en route to his inauguration in Washington, D.C. Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper sent “our resident artist” to caption the moment; the drawing shows the depot in the background and Lincoln being escorted to his carriage by John Alexander Kennedy, superintendent of Metropolitan Police (click here to see a daguerreotype of Kennedy taken by Mathew Brady):

Abraham Lincoln’s Special Inaugural Train at the Hudson River Railroad Depot, 1861. From Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, courtesy Library of Congress

What’s so haunting about this story is that four years later, on April 25, 1865, Lincoln’s funeral train passed through the depot again on its westward journey to Springfield, Illinois.

High above that hallowed, historic ground, is one of the largest green roofs in the United States. It’s a perfect spot to contemplate the history all around you. The garden, which was designed by landscape architect Elizabeth Kennedy and built by Michael DiMezza, is one of the most beautiful inaccessible places in New York City. Employees of the postal service use the 2.5-acre roof park during lunch and coffee breaks, but the several times I’ve been there it has been virtually empty. Except for one day last spring when a new family of Canada geese had taken up residence:

This was one of the first green roofs in Manhattan, and it has served as a model for many other projects since its completion. The garden is filled with mostly native plants and the landscaping was designed to help reduce storm-water runoff in the city’s sewage system.

It’s a beautiful place during every season of the year, and a great perch from which to enjoy 360-degree views of Manhattan and the Hudson River. And it has more than just a historical connection to the High Line: seeds from the linear park’s garden have hitchhiked to the roof of the Morgan — carried by the wind or in bird poop — and established themselves in the postal service’s less crowded rooftop garden. Maeve Turner, a gardener at Friends of the High Line, identified the dandelion-like plant below as Tragopogon dubious, or yellow salsify. It turns out that this specimen is also a volunteer on the High Line; it appeared for the first time in the park in 2012, in the Wildflower Field, which is just below the Morgan and runs along Tenth Avenue from around 27th – 30th Streets. But the plant had been found in the still-wild section of the High Line at the Rail Yards since at least 2004. This of course is one of the main themes in the story of the High Line: a “self-seeded” landscape grew up in the abandoned viaduct, filled with plants that came from all over the country and the world. Now the High Line itself has become a leaping-off place for seeds in search of yet another urban landscape.

Today, visitors to the northern end of the High Line will find a place that has been utterly transformed since Fall 2012 when I took the picture at the top of this post and the one just below.

Morgan roof, October 2012, from the Ohm apartment building

A new city is rising above the Hudson Rail Yards (for more on the history of the railroad on Manhattan’s West Side, see the Westyard Distribution piece) and a tall residential building just across the avenue from the Morgan is almost complete. But last year, as the heavy construction was just underway, my aerial photos caught yet another story: a feisty tenement that refused to sell out to real estate developers who were acting out an ancient tradition in New York, rewriting the cityscape for profit and glory. In both photos a giant crane hovers over the small standout. Today the historic tenement shares a wall with the modern luxury building. I love the spirit of that building and hope it never comes down.

Construction on section 3, the High Line at the Rail Yards, is ongoing. When it’s completed next year, workers will turn their attention to the Tenth Avenue Spur, the last bit of abandoned railroad to become park space. When it’s completed in 2016, the only visible sign of the mail trains that will be left is the bricked-up entryway that the boxcars once passed through. Here’s a close-up of the abandoned Tenth Avenue Spur in 2012:

Below is what it looks like today, with the almost-complete residential tower on Tenth Avenue, the building that now shares a wall with a 19th century tenement.

And below is an architectural rendering of the future Tenth Avenue Spur showing “the nest,” a lush bowl that will contain a little forest of plants just above the traffic that rumbles along on Tenth Avenue.

Architectural rendering of Tenth Avenue Spur design. Image by James Corner Field Operations and Diller Scofidio+Renfro, courtesy of the City of New York and Friends of the High Line

It will be a very small garden, but like the other landscaped sections of the High Line the Spur will be an innovative, original space, a public garden unlike any other in New York City. Visitors to this unusual spot will find themselves at a particularly fine crossroads in Manhattan, a place with a richly storied past that is still in the process of reinventing itself for the future. It’s the oldest story in New York.

Click here to read more articles in the High Line Architecture series.

Great piece.

[…] Source: Livin’ The High Line […]